Vancouver’s narrative over the past two decades has often hinged on densification — how to manage the rise of dull grey towers framed by distant green mountains.

But with every megaton of carbon dioxide belched into the atmosphere, the and increasingly heavy rainfall has pushed the region toward letting more of that forest creep back into the city.

Known as “green infrastructure,” the idea is to simulate a natural water cycle wiped out from decades of city building. Besides the aesthetic benefits of more green space, positive spin-offs include mitigating flood levels, cleaning tainted rainwater for aquatic species and a general urban cooling effect that regulates temperatures at the height of summer.

“In the old days, it was 'scoop the water up and send it down these pipes.' Now, with climate change, we have to restore these old systems,” said Melina Scholefield, the City of Vancouver’s manager of green infrastructure implementation.

“That’s the whole paradigm shift.”

From Hope to Richmond, British Columbians have destroyed or buried at least 117 streams along the Lower Fraser River. Another 50 per cent of streams are endangered due to human activity, and many more have been channelized or diverted to make room for everything from farms and shopping malls to roads and condo towers.

That’s had massive implications for salmon. Between 1980 and 2014, the Fraser averaged 9.6 million sockeye returns annually, but the last two years saw some of the worst returns in the river’s history, bottoming out at 485,000 in 2019, the lowest since record-keeping began in 1893.

Localized flooding like this seen near Still Creek in Burnaby in 2018 is only likely to become more common as climate change leads to heavier rainfall and rising seas. By Cornelia Naylor/Burnaby Now

Localized flooding like this seen near Still Creek in Burnaby in 2018 is only likely to become more common as climate change leads to heavier rainfall and rising seas. By Cornelia Naylor/Burnaby NowLast month, a study out of Simon Fraser University (SFU) found more urban design standards around green infrastructure are needed to protect Fraser River salmon from toxic stormwater that eventually empties into rivers and streams. Enforcement, the study found, was lacking at the provincial level.

“As we face climate changes, there are going to be more intense rainstorms. This is part of the solution,” said Adeel Zafar, an SFU professor who runs the Pacific Water Research Centre at the school.

Beyond lowering in neighbourhoods like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and False Creek, Zafar said green roofs, permeable pavement and strategically placed matrices of soil and plants have been shown to eliminate more than 90 per cent of pollutants running off roadways before they hit a stream or river.

The problem, said Zafar, “How can it be implemented at a larger scale?”

VANCOUVER MOST AMBITIOUS, BUT STILL FALLING SHORT

For nearly three years, Zafar’s team has been working with several municipalities across Metro Vancouver to push the region toward an urban landscape dominated by green infrastructure.

While the and Surrey have had some success with small pilot projects, Zafar said Vancouver has led the way in the region, installing 46 pieces of green infrastructure since 2017 when it launched its Rain City Strategy. Many of those are small-scale rain gardens that use bio-engineered soils and plants hardy enough to withstand drought and flood.

Other examples can be found in a 1.2-kilometre bike path on Richards Street, where roughly 100 trees sit above a complex system of bio-soils; or at Hinge Park in Vancouver’s Olympic Village, where a “rainwater wetland” was installed in the lead up to the 2010 Olympic Games.

When a storm hits, rain doesn’t shoot across a road and into a storm drain. Instead, carefully chosen plants and soils absorb at least 48 millimetres of rainfall a day, slowly releasing the water underground or giving it a chance to evaporate back into the atmosphere.

No amount of infrastructure can control how much rain falls from the sky. But in the same way social distancing has kept hospitals from getting overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients during the pandemic, green infrastructure makes a similar promise to mitigate the worst effects of flooding.

“It’s not so much reducing the volume entering the system, but when it enters the system,” said Zafar. “This green infrastructure sort of flattens the curve.”

A deluge of rainwater might enter the sewer system in six hours through traditional storm drains and pipes; a flattened curve might spread it over a couple of days, taking pressure off already overflowing manholes.

A rain garden planted at Capilano Mall in North Vancouver slows rainwater runoff from entering the sewer system and overwhelming infrastructure. Though seemingly low-tech, the engineered gardens are expected to play a key role in preventing climate-induced flooding and cleaning tainted city water for fish. By Ben Bengtson/North Shore News

A rain garden planted at Capilano Mall in North Vancouver slows rainwater runoff from entering the sewer system and overwhelming infrastructure. Though seemingly low-tech, the engineered gardens are expected to play a key role in preventing climate-induced flooding and cleaning tainted city water for fish. By Ben Bengtson/North Shore NewsDevelopers have also experimented with high-profile green roof designs, like those found on the top of the or the new Mountain Equipment Co-op building near the corner of East Second and Quebec Street.

Though often touted as signs of a green future, Vancouver — and indeed the rest of the Metro area — is still nowhere near even its own goals: City council has adopted a 2050 target that would see rainfall filtered through green infrastructure across 40 per cent of Vancouver’s land area.

To achieve that ambitious target, Scholefield said it will require both 100 per cent adoption in new builds and widespread building retrofits on a magnitude we’re not even close to achieving.

Should we envision a post-apocalyptic city where the forest has taken over? No, said Scholefield. Green infrastructure drains city streets at a roughly one-to-20 ratio. That means three well-placed square metres of soil and plants can filter water from an area roughly equivalent to the average single-bedroom apartment in downtown Vancouver (600 square feet in 2020).

“It’s not that we’re paving the whole street green,” explained Scholefield. “But we most definitely have a long ways to go.”

Landscaping crews mow the green roof at Vancouver Convention Centre. It takes about two weeks to trim and mow the six-acres living roof, the biggest of its kind in Canada. Developers need to incorporate such designs into 100 per cent of new builds if Vancouver is to reach its 2050 green infrastructure targets, say staff. By Dan Toulgoet

Landscaping crews mow the green roof at Vancouver Convention Centre. It takes about two weeks to trim and mow the six-acres living roof, the biggest of its kind in Canada. Developers need to incorporate such designs into 100 per cent of new builds if Vancouver is to reach its 2050 green infrastructure targets, say staff. By Dan ToulgoetTHE SEATTLE MODEL

Vancouver is far from the first city to roll out such back-to-nature solutions to dampen the effects of climate change.

In the United States, a strict regulatory system requires cities to meet certain clean water milestones, punishing local governments with sometimes $10,000 fines for a single sewer overflow, Zafar told Glacier Media. That regulatory stick has pushed cities as diverse as , and , to simultaneously pursue aggressive green and traditional mega-infrastructure plans.

“In СŔ¶ĘÓƵ, it’s kind of a long-term multi-decadal view,” said Scholefield. “That is a big challenge for our city. We are reevaluating this: how do we accelerate our efforts?”

There is a real sense of urgency, both to get ahead of climate-induced flooding and to save dwindling aquatic species, like salmon.

In December, a groundbreaking study out of Washington State found particles shed by aging vehicle tires were the long-sought fatal source leading to mass die-offs of adult coho salmon. The culprit: a preservative called , added to prevent damage to tire rubber from ozone. Filter out the preservative with the right kind of plant-soil mixture and many of those deaths could be avoided, say researchers.

, an early adopter of green infrastructure, is already way ahead of its Cascadian sister to the north.

Whereas Vancouver’s combined green infrastructure projects filter roughly 32 million litres of rainwater every year, in 2020, Seattle’s rain gardens and bio-soils slowed down, cleaned and redirected over 1.5 trillion litres of rainwater, nearly 47 times that of Vancouver.

In Seattle’s drive to filter a year through green infrastructure by 2025, Zafar said policymakers have found a way to ramp up rain gardens by getting communities involved.

“You can connect to the elementary school saying we’re going to use your open space,” said Zafar. “Neighbours get excited about that and you see that peer scaling up.”

Joanna Ashworth, director of professional programs and partnerships at SFU’s faculty of environment, oversees a group of volunteer green thumbs during a demonstration of the North Shore Rain Garden Project at Capilano Mall, Sept. 21, 2019. Vancouver is looking to move beyond such pilot projects so that by 2050, 40 per cent of all land area will filter through green infrastructure. By Ben Bengtson/North Shore News

Joanna Ashworth, director of professional programs and partnerships at SFU’s faculty of environment, oversees a group of volunteer green thumbs during a demonstration of the North Shore Rain Garden Project at Capilano Mall, Sept. 21, 2019. Vancouver is looking to move beyond such pilot projects so that by 2050, 40 per cent of all land area will filter through green infrastructure. By Ben Bengtson/North Shore NewsMoney doesn’t hurt either. Seattle’s King County and public utility offer and that provide up to $1,500 to homeowners and businesses looking to install a rain garden on their property, and up to $4,500 for low-income people and non-profits.

But it’s not all from the bottom up. Regulation and accountability can also be a powerful catalyst to mobilize system-wide industry change, and multi-year descent decrees handed down from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will force a city’s hand. Metro Vancouver, said Scholefield, can learn from that.

At the same time, some cracks have emerged in the U.S. model, she said.

Because of decade-long time frames to get things done, many cities in the U.S. end up defaulting to big grey water catchment basins — like expansive underground overflow tunnels — instead of rolling out hundreds of smaller green filtration systems that slow down rainfall before it overwhelms a sewer system.

When one multi-billion dollar project fails, the results can be . And as climate change induces heavier rainfall, Scholefield said some cities will cross a threshold where building massive pieces of infrastructure .

“You can only make them so big,” said the Vancouver head of green infrastructure. “Most big cities have figured out you can’t build your way out of traffic congestion. You can’t do it with water either.”

GOVERNMENT ABSENT SINCE THE GREAT RECESSION

A big reason why Metro Vancouver is falling behind cities like Seattle on green infrastructure comes down to enforcement, concluded an April 2021 study conducted by SFU researcher Andrea McDonald.

McDonald examined 265 government documents related to water policies at the federal, provincial, municipal and First Nations level. From there, she analyzed how they lined up with a benchmark eco-certification to protect urban salmon populations.

Overall, the found local governments in Burnaby, North Vancouver, Surrey, Vancouver and Delta adhered relatively well to the , a voluntary certification program for developers, contractors and land managers to protect Pacific salmon habitat and improve water quality.

“However,” noted the report, “confusion frequently exists about what role each level of the government plays in each stage of the development process.”

According to interviews McDonald conducted with several policymakers, the СŔ¶ĘÓƵ government used to play a “significant role” in managing discussions around green infrastructure and how to manage rainwater in СŔ¶ĘÓƵ cities. But after the 2008 financial crisis, “civil servants were no longer allowed to travel to meetings or attend workshops.”

“The gradual retreat of provincial involvement in rainwater and urban watershed health management left a gap where there once was central authority providing guidance and clarity regarding the expectations and consequences for non-compliance,” concluded her report.

Private developers, meanwhile, were found to regularly treat green infrastructure as an afterthought, leading to the haphazard rollout of projects.

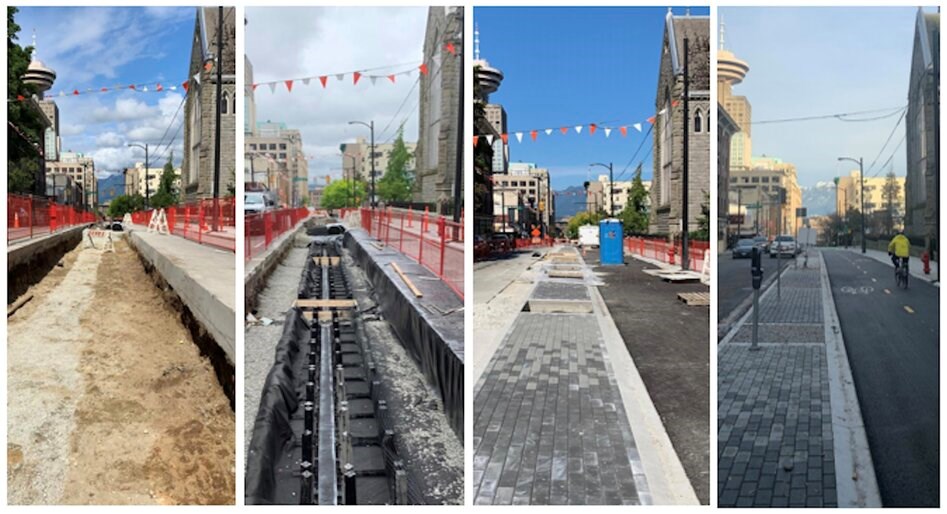

A downtown Vancouver rainwater tree trench doubles as a 1.2-km bike path on Richards Street. Once completed, the project will divert stormwater into the below-ground trenches to slowly filter water into the storm sewer system. By City of Vancouver

A downtown Vancouver rainwater tree trench doubles as a 1.2-km bike path on Richards Street. Once completed, the project will divert stormwater into the below-ground trenches to slowly filter water into the storm sewer system. By City of VancouverScholefield said Vancouver has had its own growing pains. Though it has an over 20-year history installing green infrastructure, until 2018, it was rarely done systematically and did not use geotechnical studies to understand how fast water could penetrate the ground underfoot.

“The good news is we get to learn from our peers. We get to leapfrog a bit,” she said.

Over the last three years, Scholefield said some of the biggest hurdles have been simple regulations grandfathered in from another era. In Vancouver, for example, you can’t install green infrastructure within three metres of a drinking water pipe. But with pipes coursing under one side of so many of the city’s streets, that means half the road network is off-limits.

Meanwhile, direction from Metro Vancouver, and ultimately the province, is up in the air as the regional body updates its Regional Liquid Waste Management Plan. What comes out of that will lay the regulatory groundwork for green infrastructure going forward.

“We know how to design it,” said Scholefield. “What we’re aimed at now is making it mainstream.”

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)