Homicide investigators looking for 13-year-old Marrisa Shen’s killer appear to have targeted Middle Eastern men living in the Lower Mainland in a DNA dragnet.

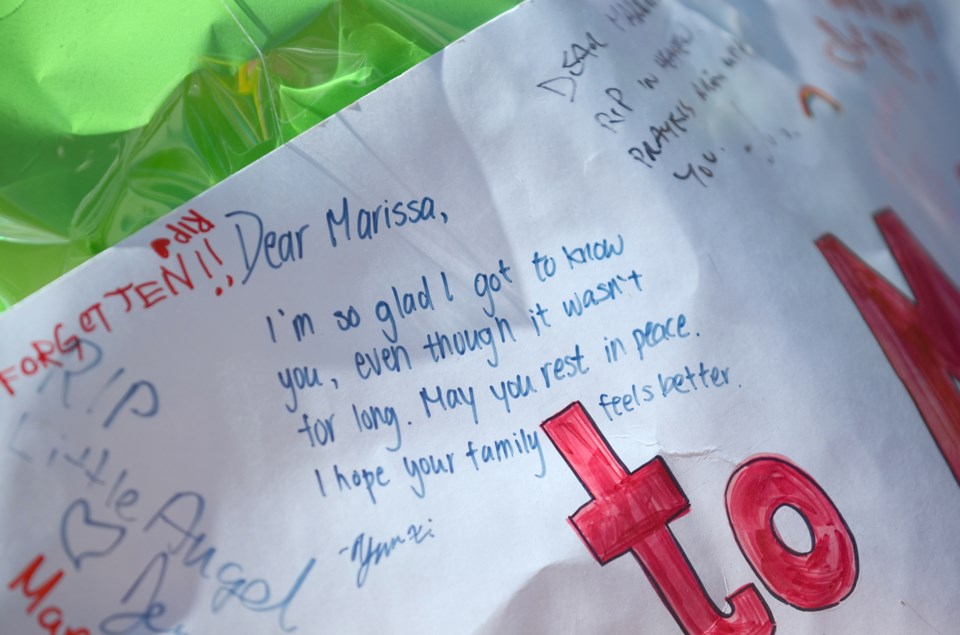

The Burnaby teen’s body was found in Central Park on July 18, 2017.

Fourteen months later, police arrested and charged a 28-year-old Syrian national, Ibrahim Ali, with her murder.

The RCMP’s Integrated Homicide Investigation Team has been tight-lipped about the techniques that led them to Ali, but the NOW has learned numerous Middle Eastern men living in the Lower Mainland – some of whom came to Canada to escape persecution in totalitarian regimes – were called up seemingly randomly and asked to provide voluntary DNA samples in relation to the killing.

“I was thinking, ‘Why me?’” Burnaby resident Ayub Faek told the NOW. “When they came, I asked them, ‘Why me?’ and they say, ‘Not only you; many people.’ I said, ‘Do you have clue like about why, for example, me?’ Maybe they have clue. They didn’t tell me. They didn’t tell me anything.”

‘For future records’

Faek, who is Kurdish, came to Canada in the early 2000s, after fleeing Saddam Hussein’s Iraq as a refugee.

“We were working for a political organization underground and we run away from there,” he said.

He said he was unnerved when he got a call from IHIT investigators who seemed to know everything about him.

“I was nervous,” he said. “And I’m sure I didn’t do anything. … This first time in my life I do this kind of interview or investigation. Never been in court or never even ask by police for anything in my life.”

Investigators called him up out of the blue, he said, and asked to see him for an interview.

At his house, they questioned him about his work, his visits to the park and Shen’s murder.

They also flashed a photo of Shen at him, he said.

“They show you a picture, to see what’s your reaction,” he said.

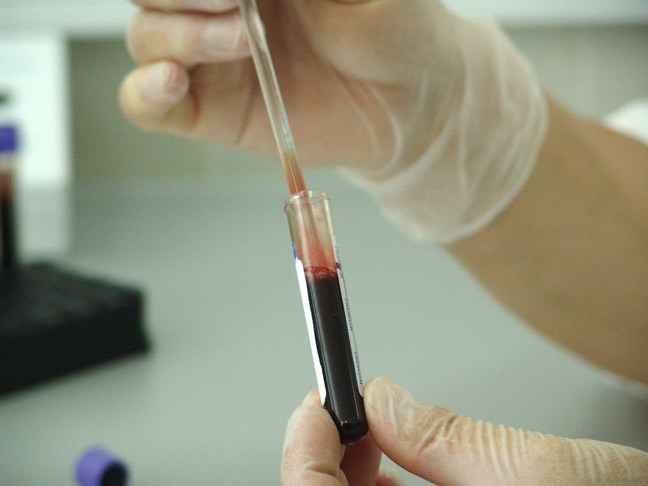

They left with a sample of blood from his finger.

“You don’t want to do that, OK, and you are no happy, but you have to say yes,” he said about the sample. “You should do whatever they want. By law, I don’t know anything. If I knew anything, I’d try it.”

Faek lives near Central Park, but he said he’s heard from other men in his community living as far away as North Vancouver and Coquitlam who were also asked to provide DNA samples.

Faek’s friend, Ariyan Fadhil, another Kurd who fled Iraq in the early 2000s, lives in North Burnaby.

IHIT called him up while he was working in West Vancouver.

They asked to see him that day and questioned him in a van during his lunch break, he said.

“I was questioning in my mind, ‘Why they are asking me?’ I’m not living in the area,” he said.

Like Faek, Fadhil said he didn’t feel like he had much choice about the DNA sample.

“I knew that, if they want, they’re going to get an order from court or something, I don’t know, to take it from me, so that’s why I gave it,” he said.

The men said IHIT promised the DNA samples would be destroyed after the investigation wrapped up, but both are skeptical.

“I was thinking that maybe they just want to collect DNA from people from Middle East for future records,” Fadhil said. “That’s what I thought. I still believe that. They said they’re going to destroy it, but I don’t believe it.”

“If you work in political, you think about many things, not only the point,” Faek said. “You think they do many things behind this or under this.”

He said he felt singled out when IHIT contacted him and, at first, didn’t want to tell anyone about being asked for his DNA.

He was relieved, he said when he found out how many other men in his community had been asked.

‘Inherently coercive’

But that raises concerns of its own, according to Abby Deshman, director of the criminal justice program for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

“It raises questions about racial profiling and the appropriateness of widespread DNA collection from a systemic perspective,” she told the NOW.

Despite being “voluntary,” Deshman said people subjected to the DNA requests find them “inherently coercive” because people who refuse then become suspects regardless of whether or not any other evidence links them to the crime.

“We question the validity of the consent,” Deshman said.

That’s especially true for vulnerable or marginalized groups, including new Canadians and refugees, she said.

She pointed to a similar case in 2013, when the Ontario Provincial Police conducted a DNA sweep of 100 racialized migrant workers in Tillsonberg, Ont.

A sexual assault victim there had described her assailant as black with what she thought was a Jamaican accent, so the OPP requested DNA samples from 100 racialized workers in the area – but many of the men did not match the height or age of the suspect. The only similarity was their skin colour.

The incident sparked a human rights complaint and an investigation by the Office of the Independent Police Director, who found the sweep had been “overly broad.”

The human rights complaint is ongoing.

Deshman said it is “deeply concerning” that Faek and Fadhil felt they couldn’t say no to the DNA request.

For the sample-taking to be truly voluntary, she said police need to do more to make individual rights and freedoms under Canadian law clear to people who have come from countries with very different criminal justice systems.

Toward that end, the CCLA wants to see DNA sweeps subject to independent oversight.

“So far, that’s not what the law requires,” Deshman said. “We don’t think they should never be used as investigative tools. There are serious crimes, and there are times when you can legitimately engage in this kind of police investigation, but we think they should absolutely be reserved for very select cases and that there should be oversight.”

That oversight should include accountability around the retention and destruction of the DNA samples.

“That is a core concern of many people who are subject to these requests,” Deshman said.

‘No further comments’

IHIT wouldn’t comment on its policy for the collection, retention and destruction of voluntary DNA samples.

Media spokesperson Cpl. Frank Jang would only say that IHIT “strictly adheres to Canadian law and RCMP policy with respect to the handling of DNA exhibits.”

During its 14-month murder investigation, IHIT said more than 1,300 residents in the Central Park area were canvassed, more 600 interviews were conducted and more than 2,000 persons of interest were identified and subsequently eliminated.

IHIT wouldn’t say whether those 2,000 persons of interest were men from the Middle East who were asked for their DNA.

“Our police investigation is complete” Jang told the NOW in an emailed statement. “It's been turned over to the courts. There will be no further comments provided.”

IHIT would not confirm whether or not a DNA sweep had been conducted, why so many Middle Eastern men across Metro Vancouver were asked to provide samples, how they were identified or whether the RCMP provided any support to men who – after escaping oppression and state-sanctioned violence in places like Syrian – might have been traumatized by being singled-out seemingly randomly by police to provide DNA for a murder investigation.

(The NOW learned of one former refugee who thought he was being targeted because he is suing someone with family in the RCMP.)

��

What did police find on scene?

С����Ƶ Institute of Technology DNA expert Dean Hildebrand said it is possible investigators found DNA at the crime scene and had it analyzed for ethnicity, much like what happens when people send a sample to a business like ancestry.com.

“Relatively geographically, it’s likely that in the Middle East your DNA profiles are going to align more closely than, say, to sub-Saharan Africa or China or European ethnicities,” he told the NOW.

Investigators may have canvassed Middle Eastern men for DNA because a crime scene sample indicated the killer or his family were from that region.

“It’s not a common test, though, in the forensic realm,” Hildebrand said. “The RCMP don’t do that routinely. They don’t have that test in-house for ethnicity.”

Hildebrand said he’s not surprised IHIT has been tight-lipped about the sweep, as police are protective of their investigative techniques.

When asked if the RCMP might be trying to dodge controversy by not making the sweep public, he said that was a question for police.

“There’s always sensitivities around privacy, but again, these are voluntary samples,” Hildebrand said, “and they can say yes, they can say no. That’s their right.”

That’s not how it felt to the Faek and Fadhil, though.

“It just raise more questions, so you have to give it right away,” Fadhil said.

Faek agreed.

“We are new to Canadian life,” he said. “We didn’t know anything about this.”

A brief history of DNA sweeps

In a DNA sweep or dragnet, police may ask hundreds, even thousands of people from a particular demographic or living in a certain area for blood or saliva in the hope of finding a match with DNA found at the crime scene.

The nature of the crime sometimes determines the target group, as it did in the first DNA sweep in 1987 in Leicestershire, England.

Investigating the brutal rape and murder of two 15-year-old girls, police there asked 5,500 local men to volunteer blood or saliva samples, leading to the arrest and conviction of local baker Colin Pitchfork.

Pitchfork had actually convinced someone else to masquerade as him to give blood, but he was found out when that person bragged about it at a pub later.

The target group might also be identified by a victim’s description of a criminal, as in an Ontario sexual assault that saw 100 racialized worker canvassed after the victim described her assailant as black with a Jamaican accent.

Even if the perpetrator doesn’t agree to provide a voluntary DNA sample, a sweep helps police by narrowing the number of possible suspects.

In 2003, police investigating the rape and murder of 10-year-old Holly Jones put software developer Michael Briere under surveillance after he refused to provide a sample.

He was arrested and convicted after they retrieved pop cans and straws he threw away and matched DNA found on them with DNA recovered from under Jones’ fingernails.

With advances in genetic science, a newer, more controversial technique, called forensic DNA phenotyping, has now also made it possible to establish some of a suspect’s visible characteristics and ancestry by comparing crime-scene DNA samples to human genetic information from various regions, such as Africa or Asia.

A DNA sweep can then be conducted of a group using that information.

��

��

��

��

��