British Columbia’s history includes the stories of many Black pioneers who came to this province seeking a life full of opportunity and promise.

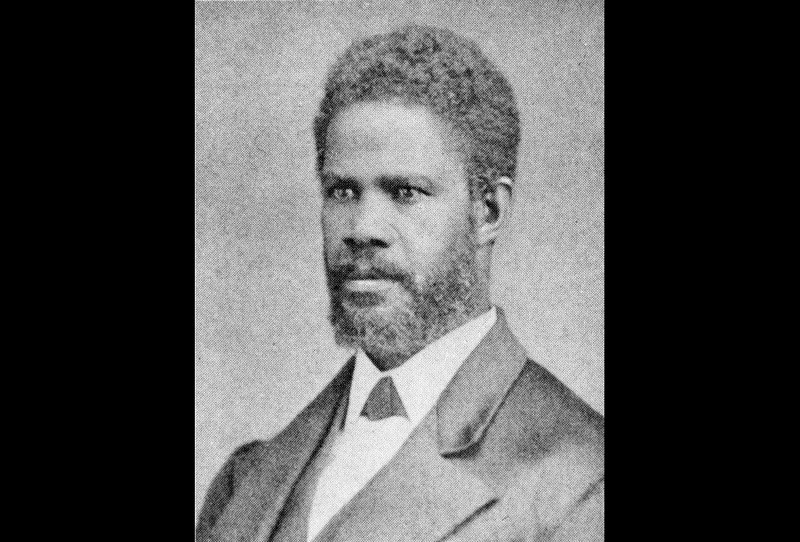

One of those pioneers was Barkerville’s William Allen Jones who was also the first dentist in –°¿∂ ”∆µ to be granted a license under the British Columbia Dental Act.

Visitors walking the streets of Barkerville Historic Town and Park will find a sign that reads: “Painless Tooth Extraction: Dr. Jones will extract teeth and perform short operations without pain.”

Dubbed “Painless Jones” in advertisements at the time, he performed dentistry services for people in the bustling town of Barkerville which was booming during the Cariboo Gold Rush.

“Well, unfortunately, we don't actually know a whole lot about him. The information we do have about him is sparse,” said Mandy Kilsby, curator at Barkerville.

“We know he was a dentist here. We know he was the first person in –°¿∂ ”∆µ to officially practice as a registered dentist when they started licensing.”

Kilsby said that dentistry at the time was practiced more like a trade before the Dental Act was passed in 1886.

“He had been practicing previously but when they introduced a new dental act, he went and got his license and continued to practice.”

Jones was granted a license on June 26, 1886, although he may have been practicing dentistry as early as 1865.

He was born in North Carolina in 1831 to his parents Allen and Temperance Jones. It is reported that Allen bought his family’s freedom from slavery for $5,000 and eventually moved the family to Ohio.

Jones and three of his brothers then attended and graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio.

After he graduated in 1859, Jones and his brothers moved to Salt Spring Island, –°¿∂ ”∆µ and then Jones and his brother Elias headed north to Barkerville when gold was discovered there.

Their brother John Craven remained on Salt Spring Island to establish a school.

In Barkerville, Jones worked as a miner and stayed eventually becoming known as the Barkerville’s Dentist or “Painless Jones”.

“He advertised in the newspaper, the Cariboo Sentinel as painless Dentistry so he would have used the patent medicines at the time to help make the process less painful for his patients,” added Kilsby.

He returned to the United States after the Civil War ended in 1865 where he visited Oberlin to continue the dental studies that he had started earlier.

While his brother Elias opted to stay in the U.S. after returning, Jones decided to venture back to his life in Barkerville.

The –°¿∂ ”∆µ Black History Awareness Society says he found a home and the kind of life he wanted in Western Canada.

The society says that most Black settlers came from western states where they were facing restrictive government legislation, ambivalence towards slavery and beatings, insults, and legalized injustice.

At the time, –°¿∂ ”∆µ’s first colonial Governor James Douglas, who was the son of a Creole woman, promised Black immigrants that they would be subject to the same laws as every other free citizen of –°¿∂ ”∆µ, as well as the same basic rights and liberties.

“Jones' family had emigrated from the United States and at the time Barkerville and the gold rush was sold as an opportunity,” said Kilsby, adding that undoubtedly Jones would have still faced discrimination in Barkerville.

“But it was a chance for a new life, new opportunities - for lots of people that didn't necessarily have them wherever home was - and kind of the same reasons that everyone came here.”

Other notable Black residents of Barkerville included barber Wellington Delaney Moses, known for being a witness in the famous murder case against James Barry who was found guilty of killing Charles Morgan Blessing, and Rebecca Gibbs who worked as a laundress but had poetry published in the newspaper.

When Barkerville was restored as a gold rush town tourist attraction, the office of Dentist Jones, complete with chair and instruments became a feature on the main street.

“The exhibit itself is a reconstructed building and the exhibit was put together with the assistance of dentists and historical tools that they would have used at the time,” said Kilsby.

“So, it's not necessarily anything that directly belonged to him, but it's meant to been to represent what would have been available to him.”

Jones died of pneumonia in 1897 in Barkerville and is buried there in the Williams Creek Cemetery.