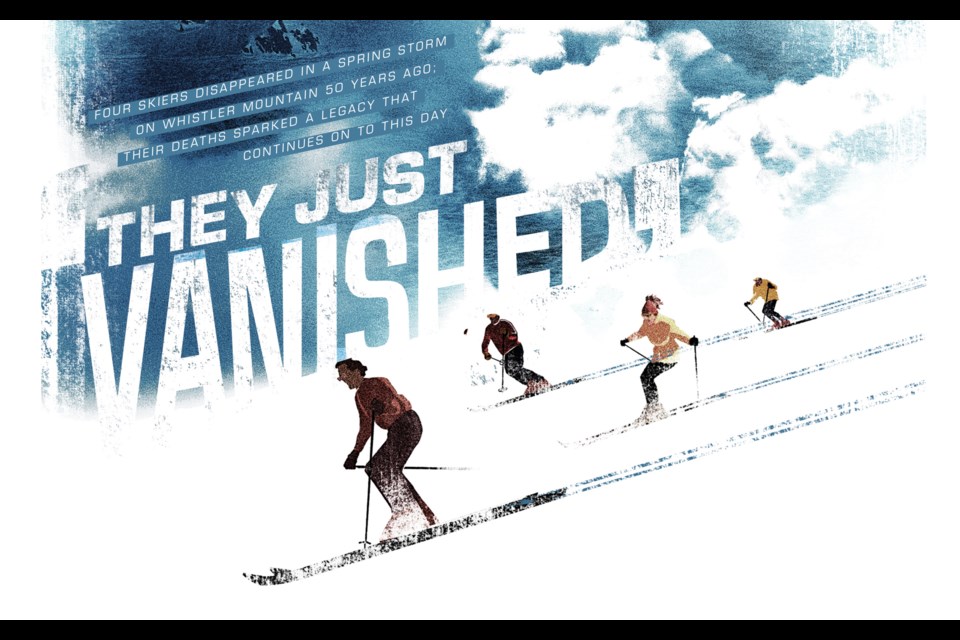

Hugh Smythe was riding up Whistler’s Green Chair when the sky around him suddenly turned white.

It was Saturday afternoon and Smythe, Whistler Mountain’s hill manager, was nearing the end of his sixth season at the resort. The lift came to an abrupt halt just before 3 p.m., and remained stopped for nearly 15 minutes as violent gusts sent chairs swinging and flurries reduced visibility to zero. The chair ahead disappeared from view. Smythe was a couple of towers away from the top terminal when the fierce snow and wind squall blew in, “the likes [of which] I’d never seen before nor in the 50 years since,” he recalls.

It was later reported that 10 centimetres of snow fell on Whistler in only an hour. The date was April 8, 1972.

Around the same time that Smythe was stranded on a chairlift somewhere above Ego Bowl, Heather Howard and her husband Peter would have been dropping into Whistler’s Back Bowl—today known as Harmony Bowl—alongside Dave McPhedran and Gerry Schlotzhauer. The skiers would have hiked over the ridge from the top of Whistler’s T-bar, no doubt trying to make the most of the more than half a metre of spring snow that had blanketed the rocky alpine terrain in the previous 48 hours.

Aside from the brief storm, that Saturday proved to be an otherwise routine day at work for the hill manager; a title that put Smythe in charge of Whistler’s ski patrol, safety, avalanche control, lift and grooming crews. It was on track to end as usual with a closing sweep of the mountain followed by a 6 p.m. meeting with the mountain’s operations manager and GM.

Until a colleague popped their head into the meeting room. Friends had reported the Howards missing after the couple failed to collect their 22-month-old son from Whistler’s on-mountain daycare service.

By 7 p.m., it would be discovered that two more skiers, McPhedran and Schlotzhauer, were unaccounted for. Though the four Vancouverites hadn’t arrived on the mountain together, the skiers had been seen chatting in the Roundhouse Lodge that afternoon.

What started as an unremarkable Saturday would eventually escalate into a massive, multi-day search effort culminating in the devastating retrieval of four bodies buried under avalanche debris in Back Bowl. The incident remains the deadliest avalanche recorded on Whistler Mountain’s slopes. In its aftermath, the tragedy served as an impetus for improved safety protocols at Whistler Blackcomb, as well as the establishment of Whistler Search and Rescue, the volunteer organization celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

“We had never had a catastrophe such as this,” says longtime Whistlerite Bryan Walhovd in an email, recalling his role in the search. “Four people skiing off into a whiteout at the top of the T-bar and then not showing up at the base of the Blue chair later. The four did not have a chance in retrospect but we, the mountain staff, ski school, and fellow skiers that day certainly tried our best.”

WHISTLER, 1972

At the time, Smythe would customarily receive reports of a missing skier about once every three weeks. “Ninety per cent of the time, they’d show up,” he says. “Either they weren’t really missing at all and they were in the bar, or they were at somebody’s house or had actually got in their car and drove to Vancouver and didn’t meet whoever they were supposed to meet.

“Up to that point I’d been on nine night searches where we actually found nine people and brought them out.”

The Whistler where Smythe began his career could almost be mistaken for an entirely different mountain compared to the resort that exists today. Half a century ago, Creekside was the resort’s only base. A lift dubbed “Blue Chair” carried skiers from near the bottom of the current Harmony Chair to the Roundhouse area, ending near where the helicopter pad sits today. Skiers cruising down the Olympic run would catch a bus by the garbage dump—now home to Whistler Village—that would bring them back to the base. Blackcomb was still eight years away from opening. There was little-to-no avalanche control carried out in the high alpine, avalanche beacons weren’t commonly used and the bulk of ski patrollers were volunteers.

In 1971-72, “There were 136,000 skier visits for the season,” says Smythe. “That’s about what we get in a busy week now.”

Peak Chair was then only a pipe dream and Highway 86 hadn’t yet been cut; meaning the few skiers seeking untouched powder lines would need to hike from the T-bar and traverse into Whistler Bowl. Those who skied the ridge down to “Far Whistler Bowl” rather than turning down Shale Slope and heading back to Red Chair would, in most cases, earn a long ride out through dense old-growth forest to the valley bottom.

Others riding the T-bar opted for the opposite side of the mountain, traversing either over Harmony Ridge or below the ridge’s cliffs to reap the deep rewards offered by Gun Barrels, before making their way back to the base of Blue Chair.

Usually, it was a safe bet that any disoriented or injured skiers could be found lost somewhere in the thick trees below either zone.

That’s precisely where Smythe assumed they’d find the four missing skiers.

THE ‘WHAT IFS’

For many of those involved in the search, one of the more puzzling aspects of the incident remains how the four missing skiers came to meet up on the mountain. The Vancouver-based professionals ran in similar circles, but were almost strangers.

Kerry McPhedran has an idea.

Prior to heading up the mountain on April 8, Dave and Kerry McPhedran had coincidently met another young couple, Heather and Peter Howard, at the opening of a local antique shop owned by Heather’s parents one evening earlier in the week. The pairs chatted about their similar interests, including weekends spent skiing in Whistler.

After a morning spent gliding through fresh snow that Saturday, Dave was ready for lunch. Kerry, on the other hand, opted to take one more run down to Red Chair before meeting him at the Roundhouse. By the time she arrived at the bottom, the lift had broken down. “It wasn’t a quick fix,” she recalls, “but no one knew that at the time so most of us waited. And waited. And waited. No cell phones.”

Kerry eventually arrived at the Roundhouse to find the pack she and Dave hung on a nearby tree missing half the lunch they’d brought. The couple had lost track of each other on the mountain before, “so I didn’t think anything of it, and ended up skiing with other people I bumped into,” she says, remembering “a massive storm” that blew in around 3 p.m. “You couldn’t see or move.”

After ending her ski day and hanging around the base a short while looking for Dave, Kerry concluded he must have run into some friends. She grabbed a ride back to their Emerald Estates cabin with the couple they shared the rental with. “Dave wasn’t the kind of guy to go off drinking and just forget everything … and so you’re [saying] ‘Where is that guy?’ And then you’re thinking, ‘Boy, you better be dead or have a good excuse,’” says Kerry, who was 28 at the time.

Then, a knock on the door. “It was somebody connected to the Howards. They said ‘Does Dave McPhedran live here? Our friends are missing, and somebody saw them together.’”

Plus, the McPhedrans’ car was still in the parking lot where they’d left it that morning.

Today, Kerry’s best guess involves another chance meeting between Dave and the couple he’d met in the antique shop just a few nights before. He knew Gerry Schlotzhauer after meeting through a social event hosted by the Vancouver financial firm where he and Schlotzhauer’s wife Angela worked, she says.

“Dave had likely heard about the Red Chair problem and knew he and I could easily keep missing each other, if he tried to ‘find me,’” says Kerry. Instead, he’d meet up with her at the base.

“That leaves the ‘what ifs.’ What if I hadn’t taken that one extra run? Would we have been a group of five? What if Dave had joined me on that extra run? What if the chair lift hadn’t broken down?”

SEARCH PARTY

Smythe’s first stop after hearing of the missing skiers was Ken Downie’s house, where a small group of friends, including Al Whitney, had just wrapped up dinner. Smythe thought the group might know the missing skiers, or have an idea of where they may have been skiing that afternoon.

“They said, ‘Hey, we’ll go up and search—we’d like to help,’” tells Smythe. “So we gave them some headlamps.”

With volunteer ski patrol alerted, about 17 people were gathered at the base of the mountain by 10:30 p.m. The overnight search party made their way to the top of the T-bar before breaking into three or four groups and heading off in different directions, Smythe remembers.

Whitney’s group hiked to the top of Shale Slope, quickly realizing the afternoon dump of snow had obscured all tracks as they descended into the evergreens below Whistler Bowl. “As we had experienced a heavy snow squall in the afternoon, we imagined our friends to be caught somewhere in the forest below either side of the mountain … Mostly at this point we were lighthearted. We had seen no avalanches, and now got only a few sluffs of the new snow,” recalls Whitney.

As those first searchers made their way up Whistler Mountain under dark skies, Smythe was sure the missing skiers were lost or injured. With skiers finding no visible avalanche debris and experiencing no avalanche activity, the possibility the missing group had been caught in a slide didn’t seem imaginable.

The search resumed at daybreak Sunday, with search parties returning to the alpine on foot and three helicopters battling variable visibility to lift off for aerial surveys of a swath of terrain stretching from West Bowl to Russet Lake. (Smythe recalls, in particular, stepping out of a helicopter near the Russet Lake hut expecting to find snow immediately underfoot. He instead dropped “10 or 15 feet” through the air, sinking up to his waist in the deep snow.)

Despite the search party swelling to 120 people—many of whom counted one or more of the four missing skiers as close friends—the mass effort again proved futile.

By 1 p.m. Sunday, the operation began to feel different than the other search efforts Smythe had been involved in. “My intuitive gut feel turned from ‘We’re going to find them’ to ‘things aren’t looking good,’” he says.

With darkness approaching and all of the areas that could be searched already covered, the teams wrapped up their first full day of searching. As all of the involved parties met to figure out a game plan for the next day, searchers concluded they were now looking for avalanche casualties.

Those assumptions were all but confirmed on Monday morning when two groups returned to West Bowl to probe new avalanche debris that had been spotted the previous day. One group triggered a significant slide from the top of the slope, narrowly missing the searchers below but taking out everything else in its path.

Meanwhile, Jim McConkey was leading a group through the Harmony Ridge area that separates Harmony and Symphony bowls, traversing high underneath the cornice line when he spotted what looked like a faint fracture line.

‘THEY FOUND SOMEONE’

A helicopter carrying a small crew was dispatched to the site where McConkey was already digging and probing a debris area. The area was 400 m west along the ridge from McPhedran, Schlotzhauer and the Howards’ last-seen point. Crews struggled to define the slide area—any avalanche deposits had been mostly disguised by the centimetres of new snow that had fallen since the slope released—but staked out a perimeter.

A dog located the first victim at 2:30 p.m. on April 10, and a second victim 30 minutes later.

“Between a half dozen of us, we dug out four frozen bodies,” explains Whitney. “It was easy to tell that they had died within seconds, or a minute at most. There had been no reason to look for a lost party.”

Smythe arrived at the search site as the first victim was recovered, where he found “an emotional and gut-wrenching but not unexpected conclusion to everyone’s efforts over the past few days and nights.”

According to the coroner’s report released later that summer, the Howards and McPhedran died of asphyxiation, while Schlotzhauer died from compression of the cervical spinal cord, all as a result of being buried in the avalanche.

“The Jury feels that blame must be attributed partly to the skiers’ adventurous nature and partly to the Lift Company by not providing adequate avalanche control and warning systems,” the coroner’s report reads. “The adverse weather conditions may also have been a contributing factor.”

Avalanche control carried out on April 5, 6, and 7 had purportedly resulted in medium-sized occurrences on north-, northwest- and northeast-facing slopes over the three days, according to an incident report written by Chris J. Stethem and Peter A. Schaerer and published by the National Research Council. A large controlled avalanche on a northeast-facing slope known for its infrequent occurrences was also recorded on the Friday, prompting ski patrol to place “closed avalanche” signs across the north side of Whistler Peak and the Kaleidoscope traverse. No slides were reported the following day, however.

That report named the presumed cause of the fatal slide as the brief snow squall accompanied by extremely strong winds experienced that afternoon.

“The avalanche was probably triggered by the skiers themselves,” the report states.

The four skiers also made the ultimately fatal mistake of crossing avalanche terrain as a group, the report notes: “If a distance of 25 to 30 m had been maintained between skiers only one or two of them would have been caught in the avalanche so that they could have been rescued immediately by the others.”

Today, navigating a slope one at a time is a basic safety strategy taught in avalanche courses. But if the group had been much farther apart during the intense snow squall, “they wouldn’t have seen each other," Smythe points out.

“These people didn’t have a chance.”

Like Smythe initially, an avalanche was the last thing to cross Kerry McPhedran’s mind after finding out her husband was missing.

“I was just so grateful for all the people who were searching,” she says, “because you’re just sort of in a stunned state … We were hanging around at the base where the ski patrol were, once they started searching that first evening, and thinking, ‘Oh boy, we’re going to have to buy a lot of beer to thank the ski patrol and all these people searching—those guys are really going to be in trouble.’ And then it just went on and on.

“You started thinking ‘What could be happening?’ The fact they just vanished was what was so puzzling. And no one seemed to be thinking avalanche, or at least they weren’t saying it,” she continues.

“When we realized it was an avalanche, I remember thinking, ‘doesn’t that happen more in Switzerland?’ It just seemed so unlikely.”

Kerry was sitting in a lodge at the base of the mountain, drinking a coffee and chatting with a newspaper reporter when word arrived.

“Somebody came in and said ‘They found someone.' And, you know, just the way they said it … you got this moment of, ‘This is not good news.’ But I still remember, for that split second, there’s sort of a bit of relief that at least you know.”

LOST AND FOUND

The avalanche marked an immeasurable trauma for the families and friends who lost their sister, mom, husbands, brothers, children, and ski partners.

Martin—Heather and Peter’s adopted son, who spent April 8 at daycare on Whistler Mountain—was eventually adopted by Peter’s brother, David Howard, and his wife Patti, and raised alongside the couple’s three boys. Heather’s brother Chris Patrick, who was just 17 at the time of her death, now serves as a mountain host in Whistler.

With 12 years between the siblings in age, “we didn’t really chum around because it was a big difference,” recalls Patrick. “One of the hardest things for me is that … we were always brother and sister, but were [only then] just becoming friends. She was wonderful.”

He still tries to ski a run down Harmony Ridge every April 8, to lay heather across the slope in honour of his sister.

But as is sometimes the case following tragedy, small silver linings gradually appeared. Following the at-times chaotic search marked by the near-miss when one group triggered a second avalanche above another team of searchers, the need for a more formal search-and-rescue group became apparent. It also prompted Whistler Mountain to examine its snow safety protocols, and served as an inspiration to have trained avalanche dogs ready to respond.

According to Smythe, there have been more than 70 million skier visits on both Whistler and Blackcomb mountains in the last 50 years. Out of those tens of millions, Smythe cannot recall one who has died in an in-bounds avalanche, while riding in open terrain at the resort, since that spring day in 1972.

“I would hate to say that if it wasn’t for this incident, then maybe there would have been another,” says Smythe.

Part 2 of this story, 'Searching for a legacy,' is available to read .

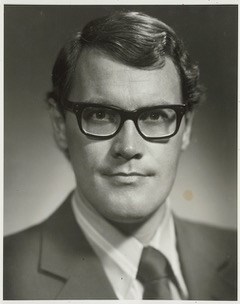

Gerry Schlotzhauer

Gerald (Gerry) Schlotzhauer was 28 years old when he died in an avalanche on Whistler Mountain on April 8, 1972, after a day of powder conditions. Skiing was one of his favourite sports, having visited resorts in Europe and North America.

After earning a Masters Degree in geography, Schlotzhauer launched his urban development career with Vancouver company Dawson Developments (later called Daon Development Corp.).

He was raised in Kitchener, Ont., where, beginning in his teen years, Schlotzhauer also enjoyed fishing, waterskiing, and his cars. Family members remember his efforts restoring an MG-TF and “babying” his GTO. Schlotzhauer left behind his wife, Angela Butcher, his parents, and four younger sisters.

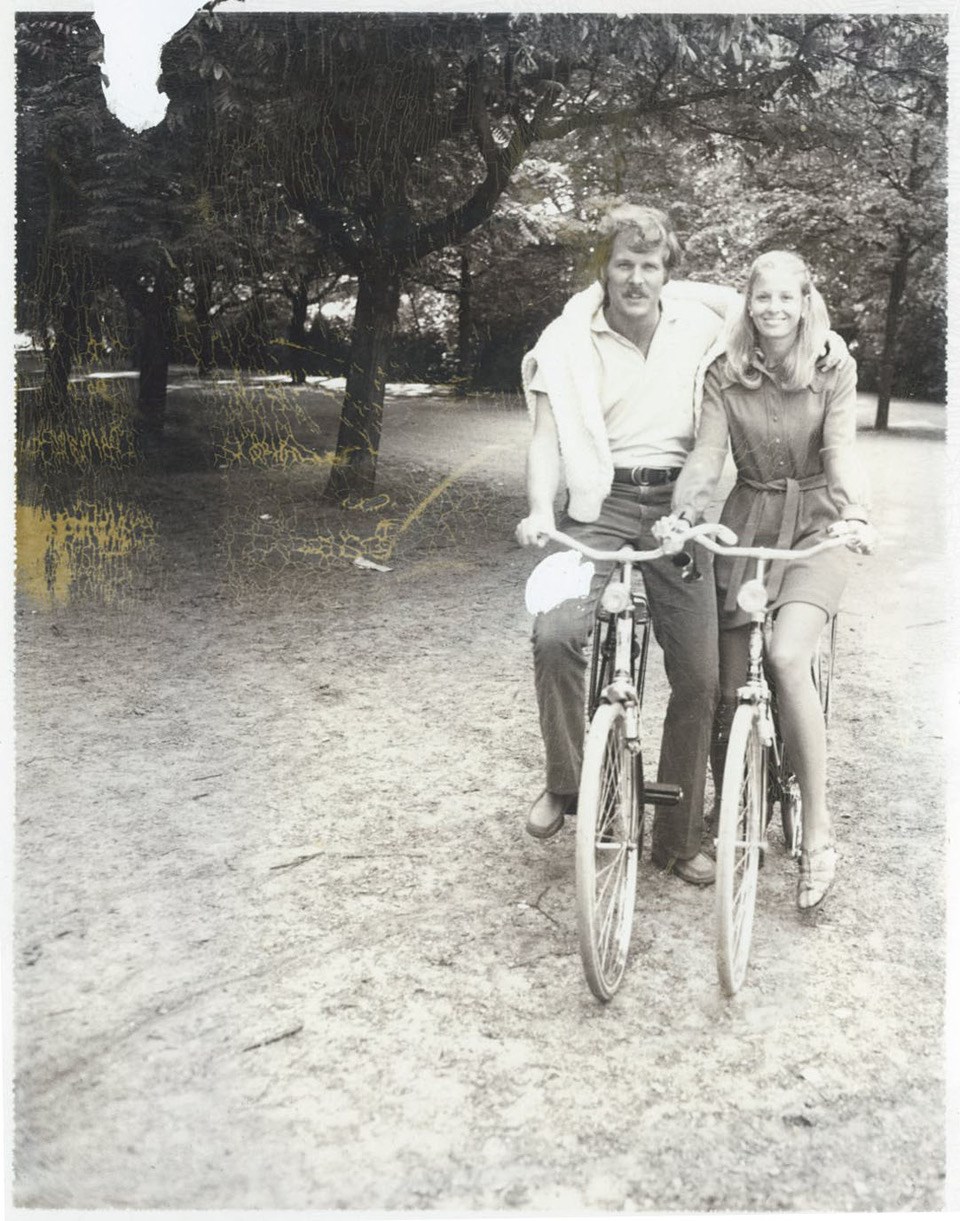

David McPhedran

David (Dave) McPhedran was 30 when he was caught in the fatal slide in Whistler’s Harmony zone.

He had married his wife Kerry four years prior; first meeting through mutual friends at U–°¿∂ ”∆µ but eventually getting together after taking the same route on their morning walks to the bus stop in Kitsilano. “We were both invited to a friend’s wedding, and Dave said, ‘Well, we’re both going, you know, why don’t we go together?’ And that was kind of the beginning of it.” (Kerry attempted to move to Europe, but Dave’s amusing letter-writing, in part, prompted her to come back. He picked her up at the airport.)

Since their wedding day, Kerry and Dave had travelled to Europe, Egypt and Greece. “Dave was the perfect traveller—open to everything and everyone, unfazed when things when sideways,” Kerry writes. In 1970, the pair “stumbled onto the perfect Greek Island,” called Sifnos. The McPhedrans were among only a handful of foreigners, while a ferry granted passage on or off the island only once every two weeks. The McPhedrans had booked two tickets back for early May 1972 and were eagerly anticipating their third trip to the destination.

The week before their last weekend in Whistler, the couple had updated their memberships with the non-profit Memorial Society of –°¿∂ ”∆µ, to record their wishes in the event of their deaths. Kerry had realized she needed to update hers after changing her last name.

Dave opted for no service and cremation. “Under ‘disposition of cremated remains’ he wrote: scattered in the Aegean,” Kerry recalls. “‘Great,’ I laughed. I’ll be in my 90s, flying to Greece with an urn!

“Little more than a month later, I was flying to Greece with Angela Schlotzhauer in Dave’s seat, and Dave in my carry-on bag.”

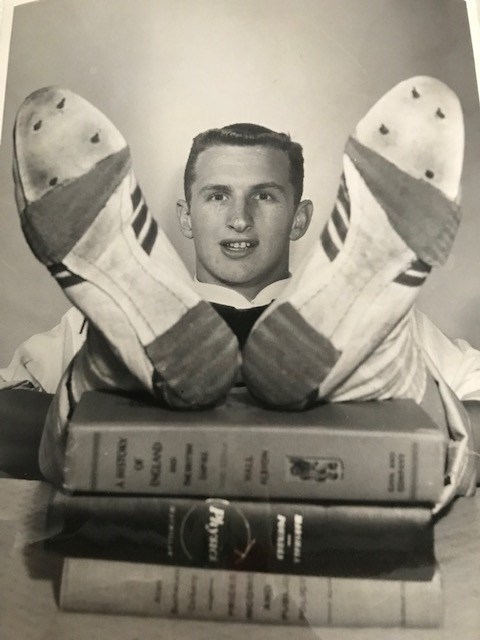

Peter Howard and Heather Patrick

Peter Howard was a gifted track and basketball athlete in his teen years, until a bout of tuberculosis in 1958 delayed his first year of U–°¿∂ ”∆µ and resulted in the loss of one of his kidneys.

Peter Howard was a gifted track and basketball athlete in his teen years, until a bout of tuberculosis in 1958 delayed his first year of U–°¿∂ ”∆µ and resulted in the loss of one of his kidneys.

It was at U–°¿∂ ”∆µ where he eventually met Heather Patrick.

“His nickname for her was ‘The Ultimate,’” says Peter’s brother, David. “They had a real fun relationship … Heather was a beautiful young lady, and very smart. And she was ahead of her time.”

Heather graduated top of her class from the physiotherapy program, while Peter graduated second in his class to earn a law degree. Peter soon joined major law firm Lawson Lundell, where he became the firm’s youngest tax partner. Peter had also attended Harvard University for a master’s in law, where he met and struck up a friendship with Bill Dickson. Peter ultimately recruited Dickson to Lawson Lundell, and convinced him and his wife Nancy to make the cross-country move from Halifax.

“When Bill and I received a letter in March, 1968, saying that they had been up skiing at this new mountain called Whistler in a foot of fresh snow on Saturday and then had come back to Vancouver on Sunday to play six sets of tennis outside, we decided to relocate to the West Coast,” writes Nancy.

The couples, both with sons born in 1970, rented a cabin together alongside another colleague, his wife and twin daughters, during the 1970-71 ski season. The women would take turns watching the kids while the others headed out on the hill, mimicking their weekday arrangements.

“Heather and I were each juggling children and careers, Heather as a physiotherapist at [Vancouver General Hospital] and I, as a social worker,” recalls Nancy. The pair arranged three-day workweeks, where, on the other two days, they’d take turns looking after each other’s sons—“a wonderful arrangement where the boys became like brothers,” says Nancy.

Bill helped participate in the search following the avalanche, which Nancy calls “the most traumatic event we have ever experienced.” Nevertheless, the Dicksons are now in their 54th Whistler ski season. “As we ski across the breadth of Harmony Bowl, we always remember our dear friends and the price they paid for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”