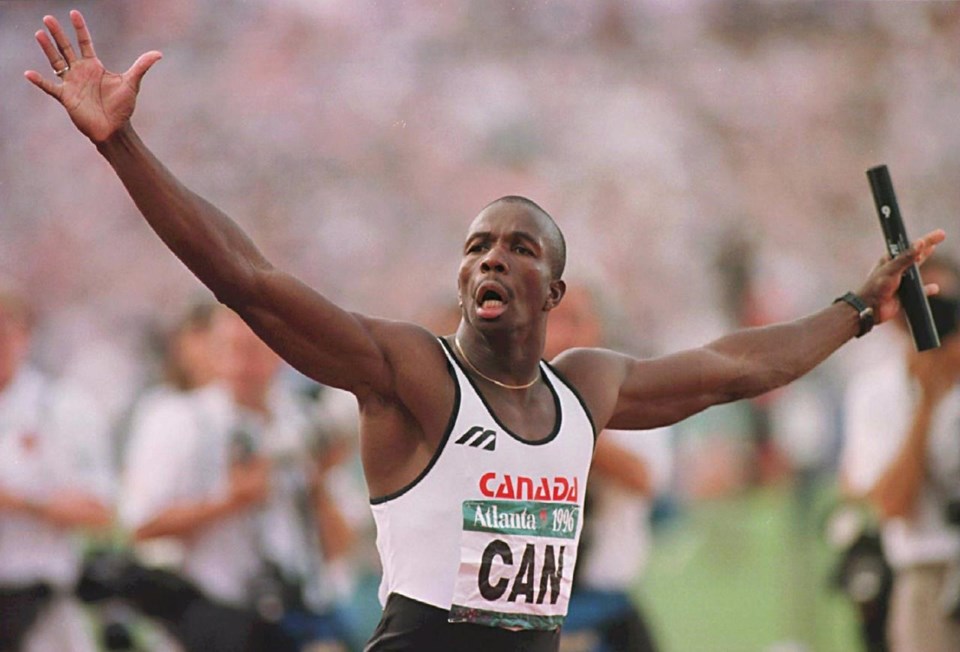

ItŌĆÖs a promise fulfilled for Donovan Bailey.

The former 100-metre world-record holder and 1996 Olympic double gold medallist is set to release his book ŌĆ£Undisputed: A ChampionŌĆÖs LifeŌĆØ on Tuesday.

ŌĆ£I promised myself one day IŌĆÖd take my story back, tell it in my own way. And thatŌĆÖs exactly what IŌĆÖve done,ŌĆØ he said in the book's prologue.

Bailey said the importance of telling his story from his own perspective wasnŌĆÖt to "find votes," or change people's opinion of him.

ŌĆ£There's some that I needed to do it for, for the people that really don't know me but have seen and heard and read the narrative,ŌĆØ Bailey said in an interview with The Canadian Press.

ŌĆ£So I thought it was very important for my children, my family, the greatest supporters that I've had. Mind you, they know my real story. But it is important, you know, for the young athletes that's represented this country to also understand or the young athletes that are global stars that represent this country need to understand.ŌĆØ

The book details his journey growing up in Manchester, Jamaica as the fourth of five sons to father George and mother Daisy, and coming to Canada in 1980. His first love was basketball, and he didn't take track and field nearly as seriously.

His unique journey back into track and field came along with troubles in progressing on the Canadian national team, highlighted by one of a couple of turning points in his career leading up to and at the 1993 world championships in Stuttgart, Germany.

He expected to run in the 100, 200 and 4x100 relay for Canada at those worlds, before finding out from then-Canada coach Mike Murray that he would be on the relay squad alone. That also did not end up happening.

ŌĆ£His justification was that the guys ahead of me had posted better times. I had a serious problem with that,ŌĆØ he wrote. ŌĆ£Back then, administrators, coaches and athletes could do what I like to call a ŌĆścreate-a-track-meet.ŌĆÖ

ŌĆ£They would put together small competitions in random locations ŌĆ” with little fanfare. The meets werenŌĆÖt advertised, and many times, elite sprinters such as myself werenŌĆÖt invited. So that presented lighter competition which an athlete could post superior times.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The bottom line was that guys who had never beat me head-to-head were all of a sudden beating my times when I wasnŌĆÖt on the track,ŌĆØ he added.

Bailey ŌĆ£cussed outŌĆØ Murray for it later that day, before fellow sprinter Glenroy Gilbert tried to calm him down and allowed Bailey to vent to him. But a declaration came out of it that rang true years after.

ŌĆ£When IŌĆÖm the king here and I run (things), this will never happen.ŌĆØ

Bailey went on to leave a well-paying job in TorontoŌĆÖs financial district along, and put his real estate portfolio in the hands of somebody else to manage, to join coach Dan Pfaff in Baton Rouge, La., in 1994. The move helped lead him to two Olympic gold medals and four world championship medals (three gold, one silver) between 1995 and 1997.

He also touched on his comments regarding the racial issues in Canada leading up to the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, which he faced blowback for.

ŌĆ£There are a lot of things that I spoke about in the '90s that are very relevant today,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£So how I was treated, you know, some of the very people that I helped along the way, you know, there's just a lot of things are relevant now.

ŌĆ£I mean, people can discuss race, people can discuss class. There's more conversations now about that.ŌĆØ

Some media referred to Bailey as ŌĆ£unCanadianŌĆØ after he called American 200-metre Olympic champion Michael Johnson a "chicken" after their their infamous 150-metre clash at Rogers Centre, then known as SkyDome, in 1997.

Johnson, who was losing the race, pulled up at the 110-metre mark with an apparent injury.

ŌĆ£We were gladiators, the 100 metres back in the day when I competed, it was heavyweight boxing,ŌĆØ Bailey said. ŌĆ£The guys might smile at each other off track and maybe even go out for dinner or something. But on the track, I mean, it was just a different thing.ŌĆØ

Despite it all, including criticisms for being arrogant, he says he has always been at peace and comfort.

ŌĆ£That was part of the problem, I was way too comfortable winning, way too comfortable training, way too comfortable giving an interview, way too comfortable being my authentic self,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£And with that, because no one's ever been like that, especially representing this country, there was lots of blowback because people, they really didn't understand that.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£To me, my story is not a Canadian story, so you know, to be the fastest man on Earth, to be a world champion, to be world-record holder, it is a global thing,ŌĆØ he added.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 26, 2023.

Abdulhamid Ibrahim, The Canadian Press