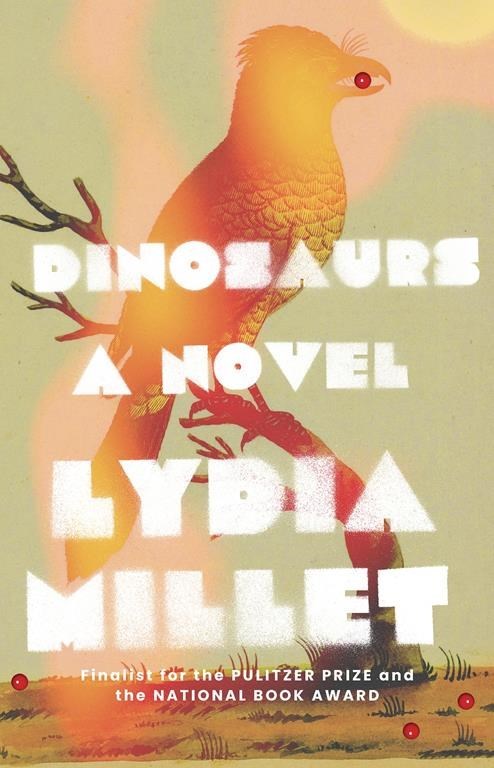

“Dinosaurs,” by Lydia Millet (W.W. Norton)

Besides moving on from a bad breakup, Gil, the protagonist of Lydia Millet’s “Dinosaurs,” walks from New York to Phoenix because he “wanted to pay for something.” He explains this to his new next-door-neighbor, Ardis, and her best friend, Sarah, over drinks later into this resettlement, saying, “When you have a lot of money, you never pay for anything. You never feel the cost, so you live like everything is free. There’s never a trade-off. Never a choice or a sacrifice, unless you give up your time. I wanted the change to cost me. You know? I wanted to earn it.”

This search for redemption is rooted in the inheritance he received from his oil baron grandparents, and his attempt to earn it manifests in a philosophy of charity. It’s the least he can do for the legacy that earned his family billions on others’ backs and for all the suffering that exists around him. Narrating between his past in New York and his present in Arizona, readers follow Gil’s previous charity at a refugee center, where fellow volunteers became some of his only friends and the language barrier satisfied his avoidance of interaction, to his current position as a bodyguard for traumatized women at a women’s shelter.

He also gives his time to the next door family, which becomes an extension of his. Ardis, a psychotherapist, is married to Ted, a developer of sorts, and they have two children — angsty adolescent Clem, and sweetly boisterous Tom. He becomes a babysitter-friend to Tom, exerting a parental protectiveness throughout a stifled world — picking him up from a martial arts class early upon seeing an instructor’s swastika tattoo, helping him navigate the neighborhood’s anti-skateboarding rules, and standing up to his bully, and his bully’s bully. In his friendship with Tom’s parents, he is slowly entangled in their own marital challenges besides their lives, as he partners with Sarah despite his earlier attempts to maintain a friendship.

Gil reflects on his volunteer friends from before, one who swore like a sailor and was in the military, the other a devout Catholic. He thinks about Lane, who ghosted him after a decade-long relationship. He contemplates his painful childhood, treating the man who contributed to some of that damage with a steady charity.

Importantly, birds take readers through these relationships, the animal’s prehistoric antecedent the novel’s namesake. One of the few things Gil noticed on his walk to Phoenix, birds structure the novel literally, a different species titling each chapter and appearing throughout the plot’s development. The hummingbirds set up Gil and Ardis’ friendship when she brings him a feeder and continues to replace the nectar, the raven that reflects a new friend’s identity and love-life aspirations, the hawk that sharpens his quest for whoever is illegally hunting quails at night. The way these birds journey together and build upon one another’s human counterparts is where the novel’s authenticity and beauty lie.

Gil’s insightful rumination bring the writing its life and the characters their development. “A kid was like an ornamental vase placed awkwardly at the edge of a doorway. You stubbed your toe on the darn thing every time you passed,” explains Gil’s childless life. Yet he is later touched by Tom, “a small boy’s condolences.” The solitude of the hawks and vultures he notices on his route, “only broken by courtship and breeding,” like his own solitude that he admits to feeling along with fear as “waves that often stopped his from remembering the one thing. The one thing and the greatest thing.”

While Millet shines light on the timely theme of taking responsibility for the world we’ve inherited is vital, these larger questions the novel hints at — the infinite, love’s intangibility, the stains of evil — leave readers hanging as she wrangles them into simplistic, flat turns of events. The anticlimactic slice-of-life frame of Gil’s character never quite substantiates the sweeping, all-encompassing conjecture at which he gradually arrives. Sparse writing creates mystery but also hinders the possible intricacies of the outcome. For all the novel’s transcendence through the past's burdens and the goodness of small acts, its convictions don’t go far enough.

Amancai Biraben, The Associated Press