ST. PAUL, Minn. (AP) — The political fight is only getting fiercer over whether it’s financially wise or “woke” folly to consider a company’s impact on climate change, workers’ rights and other issues when making investments.

Republicans from North Dakota to Texas are ramping up their criticism of “ESG investing,” a fast-growing movement that says it can pay dividends to consider environmental, social and corporate-governance issues when deciding where to invest pension and other public funds. At the same time, Democrats in traditionally blue states like Minnesota are considering whether to make ESG principles an even bigger part of their investment strategies.

The “E” for environment component of ESG often gets the most attention because of the debate over whether to invest in fossil-fuel companies. In the wide-ranging social, or S, bucket, investors look at how companies treat their workforces, reckoning a happier group with less turnover can be more productive. For the G, or governance aspect, investors make sure companies’ boards keep executives accountable and pay CEOs in a way that incentivizes the best performance for all stakeholders.

The ESG industry has scorekeepers that give companies ratings on their environmental, social and governance performance. Poor scores can steer investors away from companies or governments seen as bigger risks, which can in turn raise their borrowing costs and hurt them financially.

Florida has become one of the hottest battlegrounds for ESG. Gov. Ron DeSantis in August prohibited state fund managers from using ESG considerations as they decide how to invest state pension plan money. And even as his state cleans up from the environmental destruction caused by Hurricane Ian, DeSantis plans to ask the Florida Legislature in 2023 to go even further by prohibiting “discriminatory practices by large financial institutions based on ESG social credit score metrics.”

Pension funds are often caught in the middle of the battles. Questions are flowing into the Florida Education Association from teachers about what DeSantis’ moves will mean for their retirements.

“I usually tell them it’s still unclear what this exactly means,” said Andrew Spar, president of the union, which represents 150,000 teachers and educators across the state. Much is still to be determined, including exactly which funds the pension investments will steer toward.

In contrast, the Minnesota State Board of Investment is considering a proposal to adopt a goal of making its $130 billion in pension and other funds carbon-neutral. The board already uses shareholder votes to advance climate issues. It seeks out climate-friendly investment opportunities and eschews investments in thermal coal. While the new proposal goes farther, it does not call for total divestment from fossil fuel companies, as many climate change activists advocate.

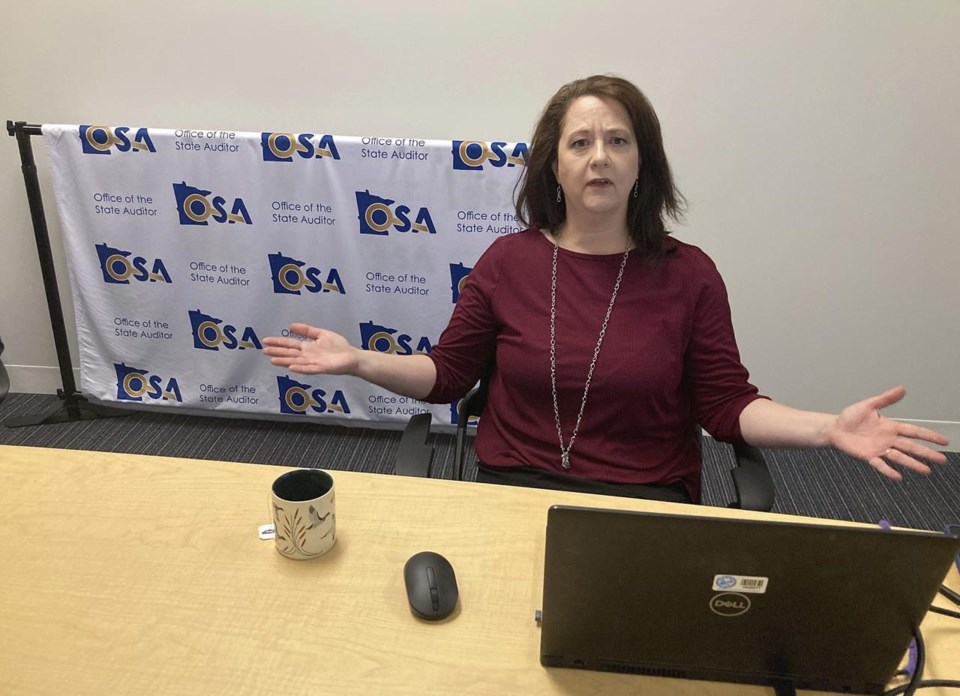

The ESG debate has spilled into the race for Minnesota’s state auditor. Democratic incumbent Julie Blaha — who has singled out DeSantis as one of the leaders she believes are politicizing the discussion about ESG — has cited the investment board’s high returns in recent years as evidence the approach works.

“To be a good fiduciary, you have to consider all the risks, and the evidence is clear that climate risk is investment risk,” Blaha said.

But Blaha’s Republican challenger, Ryan Wilson, says investment returns must come first, and that all risks must be considered. He says the board shouldn’t “disproportionately dictate” that climate risk should matter more than other risks.

Proponents say considering a company’s performance on ESG issues can boost returns and limit losses over the long term while being socially responsible at the same time. By using such a lens, they say investors can avoid companies that are riskier than they appear on the surface, with stock prices that are too high. An ESG approach could also unearth opportunities that may be underappreciated by Wall Street, the thinking goes.

As for returns, there is no consensus on whether an ESG approach means lower or higher returns.

Morningstar, a company that tracks mutual funds and ETFs, says slightly more than half of all sustainable funds ranked in the top half of their category for returns last year. Over five years, the showing is better with nearly three-quarters ranking in the top half of performers in the category.

Rejecting ESG can be costly in ways besides investment performance.

A Texas law that took effect in September 2021 banned municipalities from doing business with financial institutions that have ESG polices against investments in fossil fuel and firearms companies, industries that are important to the Texas economy. It turned out to be an expensive decision.

Barred from underwriting local jurisdictions’ municipal bonds, five big underwriters — JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Bank of America and Fidelity — exited those markets. A Wharton School study estimated that the loss of those big players would cost Texas communities an extra $303 million to $532 million in higher interest payments on their bonds. Fidelity says it has since restored its good standing with Texas by certifying to the state that it does not boycott energy companies or discriminate against the firearms industry.

Several big Wall Street banks and investment management companies have become favorite targets of the anti-ESG politicians because they’ve been outspoken in their embrace of ESG. Republican state treasurers have pulled or plan to pull over $1.5 billion this year out of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment company, which has a goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner. Missouri last month became the latest. Treasurer Scott Fitzpatrick accused BlackRock of putting the advancement of “a woke political agenda above the financial interests of their customers.”

Coal-producing West Virginia passed a law in June that allows for the disqualification of banks and other financial institutions from doing business with the state if they “boycott” energy companies. Treasurer Riley Moore soon banned BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo, blaming them for contributing to high energy prices by driving capital away from the industry.

“We’re not going to pay for our own destruction,” Moore said.

State officials have also been critical of ESG scores from ratings agencies and other outfits. For instance, S&P Global offended North Dakota State Treasurer Thomas Beadle because it rated the state as “neutral” for social and governance metrics but “moderately negative” for environmental factors because its economy and budget rely heavily on the energy sector.

His state’s lawmakers last year prohibited their investment board from considering “socially responsible criteria” for anything but maximizing returns. Beadle told senators considering potential next steps that ESG has created “significant headwinds” for energy companies trying to raise capital, and that it could affect his state’s tax revenues.

Besides state capitols, other big battlegrounds are federal agencies, where leaders of the backlash include the State Financial Officers Foundation, a group of Republican state treasurers, auditors and other officials. They’re trying to block rules being drafted at the Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Labor to require standardized climate disclosures by companies and to make it easier for pension plan fiduciaries to consider climate change and other ESG factors.

The industry has heard the pushback and has even been surprised by how quickly it’s accelerated. But it’s pledging to plow ahead.

US SIF is an industry group advocating sustainable investing whose members control $5 trillion in assets under management or advisement. Its CEO, Lisa Woll, believes that most of the national and state politicians railing against ESG investing probably don’t understand it.

“If they did, it’s very difficult to make these kinds of allegations,” Woll said. “It feels more like a talking point than an informed critique.”

___

Choe reported from New York.

Steve Karnowski And Stanley Choe, The Associated Press