Since its debut in 1971, an anti-pollution ad showing a man in Native American attire shed a single tear at the sight of smokestacks and litter taking over a once unblemished landscape has become an indelible piece of TV pop culture.

It's been referenced over the decades since on shows like “The Simpsons” and “South Park” and in internet memes. But now a Native American advocacy group that was given the rights to the long-parodied public service announcement is retiring it, saying it has always been inappropriate.

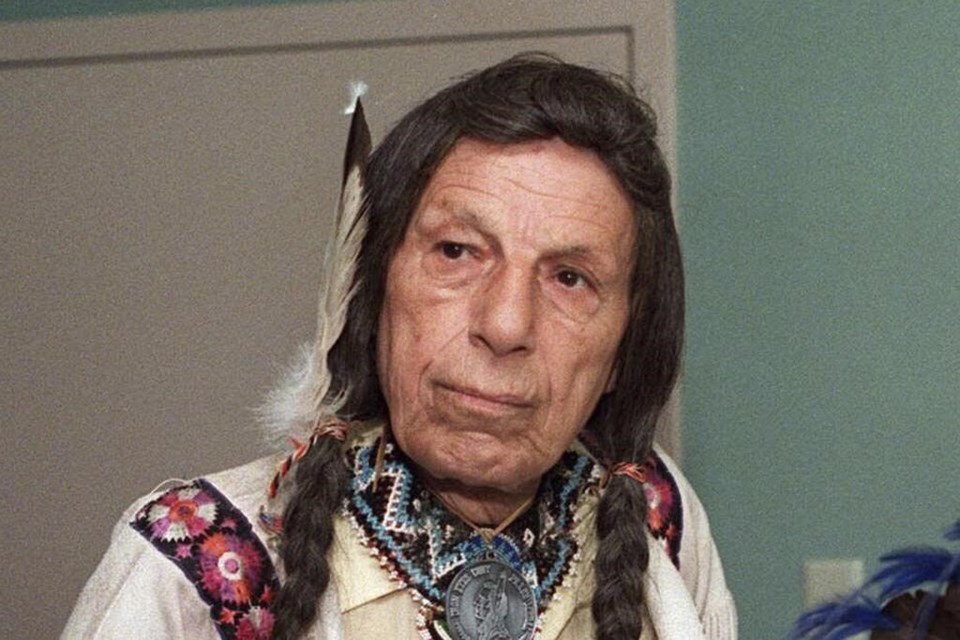

The so-called “Crying Indian” with his buckskins and long braids made the late actor Iron Eyes Cody a recognizable face in households nationwide. But to many Native Americans, the public service announcement has been a painful reminder of the enduring stereotypes they face.

The nonprofit that originally commissioned the advertisement, Keep America Beautiful, had long been considering how to retire the ad and announced this week that it's doing so by transferring ownership of the rights to the National Congress of American Indians.

“Keep America Beautiful wanted to be careful and deliberate about how we transitioned this iconic advertisement/public service announcement to appropriate owners,” Noah Ullman, a spokesperson for the nonprofit, said via e-mail. “We spoke to several Indigenous peoples’ organizations and were pleased to identify the National Congress of American Indians as a potential caretaker.”

NCAI plans to end the use of the ad and watch for any unauthorized use.

“NCAI is proud to assume the role of monitoring the use of this advertisement and ensure it is only used for historical context; this advertisement was inappropriate then and remains inappropriate today,” said NCAI Executive Director Larry Wright, Jr. “NCAI looks forward to putting this advertisement to bed for good.”

When it premiered in the 1970s, the ad was a sensation. It led to Iron Eyes Cody filming three follow-up PSAs. He spent more than 25 years making public appearances and visits to schools on behalf of the anti-litter campaign, according to an

From there, Cody, who was Italian American but claimed to have Cherokee heritage through his father, was typecast as a stock Native American character, appearing in over 80 films. Most of the time, his character was simply “Indian,” “Indian Chief” or “Indian Joe.”

His movie credits from the 1950s-1980s included “Sitting Bull,” The Great Sioux Massacre," Nevada Smith, “A Man Called Horse” and “Ernest Goes to Camp." On television, he appeared in “Bonanza,” “Gunsmoke” and “Rawhide” among others. He also was a technical adviser on Native American matters on film sets.

Dr. Jennifer J. Folsom, a journalism and media communication professor at Colorado State University and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, remembers watching the public service announcement as a child.

“At that point, every single person who showed up with braids and buckskins, on TV or anywhere in the movies, I glommed on to that because it was such a rare thing to see,” said Folsom, whose areas of study include Native American pop culture. “I did see how people littered, and I did see how the creeks and the rivers were getting polluted.”

But as she grew up, Folsom noticed how media devoted little coverage to Native American environmental activists.

“There’s no agency for that sad so-called Indian guy sitting in a canoe, crying,” Folsom said. “I think it has done damage to public perception and support for actual Native people doing things to protect the land and protect the environment.”

She applauded Keep America Beautiful's decision as an “appropriate move.” It will mean a trusted group can help control the narrative the ad has promoted for over 50 years, she said.

The ad's power has arguably already faded as Native and Indigenous youths come of age with a greater consciousness about stereotypes and cultural appropriation. TikTok has plenty of examples of Native people parodying or doing a takedown of the advertisement, Folsom said.

Robert “Tree” Cody, the adopted son of Iron Eyes Cody, said the advertisement had “good intent and good heart” at its core.

“It was one of the top 100 commercials,” said Robert Cody, an enrolled member of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in Arizona.

And, it reminded him of time spent with his father, said Cody, who lives at Santa Ana Pueblo in New Mexico.

“I remember a lot, even when he went on a movie set to finish his movies and stuff,” Cody said. “I remember going out to Universal (Studios), Disney, places like that.”

His wife, Rachel Kee-Cody, can't help but feel somewhat sad that an ad that means so much to their family will be shelved. But she is resigned to the decision.

“You know, times are changing as well. You keep going no matter how much it changes,” she said. “Disappointment. ... It'll pass.”

___

Tang is a member of The Associated Press’ Race and Ethnicity team. Follow her on Twitter at .

Terry Tang, The Associated Press