Summer in С����Ƶ is about to get a lot hotter.

In Vancouver, a changing climate is expected to increase the number of five-fold by 2050. And in Kelowna, forecasts show the city is likely to face the and hotter maximum temperatures of any major Canadian city.

How to confront that hot new reality can be paralyzing, both for local communities and households.

The С����Ƶ government has tried to push air conditioning units into the apartments of the province’s most vulnerable people.

Big cities are reconsidering how to rebalance a gap in natural shade as in the face of development. Some planners say cities need to upend old habits that cast all building shadows as a bad thing.

But for anyone looking to make in their own backyard, picking the right plant at a nursery can be a complicated task.

How do you strike a balance between cost and ensuring that once grown, the plant will actually help lower backyard temperatures? Will that tree survive the coming climate? Might it burst into flames during a wildfire? Could it poison the kids?

It’s a long list of what-ifs, one that has finally been answered in a new С����Ƶ that guides readers to the 33 best plants, trees and shrubs to ward off incoming heat while having fun.

Susan Herrington, co-author of the guide and a professor in the School of Architecture and Land Architecture at the University of British Columbia, said her team narrowed down the list after a painstaking process that considered a number of potential benefits.

“A tree isn’t just a tree. There are all different types, with different histories, uses, and values,” she said.

Take the native arbutus tree, said Herrington, whose broad, waxy leaves provide “heavy” UV protection, according to the guide.

Every year, the papery bark sheds off the fire-resistant tree, offering an ideal material for arts and crafts for children. Its berries are an important food for birds and small mammals; its flowers, an attractive meal for pollinators like bees and hummingbirds.

“It’s evergreen all year round, but it’s got the shape of a deciduous tree. You can do things under it. They grow quite quickly,” Herrington said.

And when it comes to cooling, the arbutus has even been nicknamed the “refrigerator tree.”

“You put your hand on it and you can actually feel the cool water and minerals on it moving up the tree,” said Herrington.

Need something that grows even faster? How about the paper birch? A deciduous pioneer species, the tree shoots up at 1.6 metres per year.

Or consider Pacific dogwood, a tree whose wood has long been used by Indigenous people to fashion harpoon shafts, and with a flower showy enough to take on the title as С����Ƶ’s official floral emblem in 1956.

Whether it’s the aromatic fox grape, the climate-resistant ginko tree, or the acorn-laden pin oak, Herrington says pick the shrub you think is the most interesting and would fit your home.

“We’re thinking about the growth of cities. City building is not just about building,” she said. “It’s looking at your long-term planning.”

How plants lower temperatures

Unlike the forests and fields of rural land, cities tend to be built of hard surfaces like concrete, brick, asphalt and steel — all of which absorb shortwave energy from the sun before emitting it back into a bubble of urban heat.

Known as the heat island effect, under calm and clear conditions, the phenomenon can lead to an 8 C increase in overnight temperatures.

Enter anything green. Compared to hard surfaces, grasses, shrubs and trees all tend to better reflect sunlight’s shortwave radiation, lowering the temperature felt by anyone in the area.

As plants grow, they also pull water up their stems and into their woody and leafy extremities. Here the water evaporates into the air through openings in the plant. That phase shift consumes ambient energy and instantly drops temperatures between 0.5 and 7 C, according to multiple carried out in cities around the world.

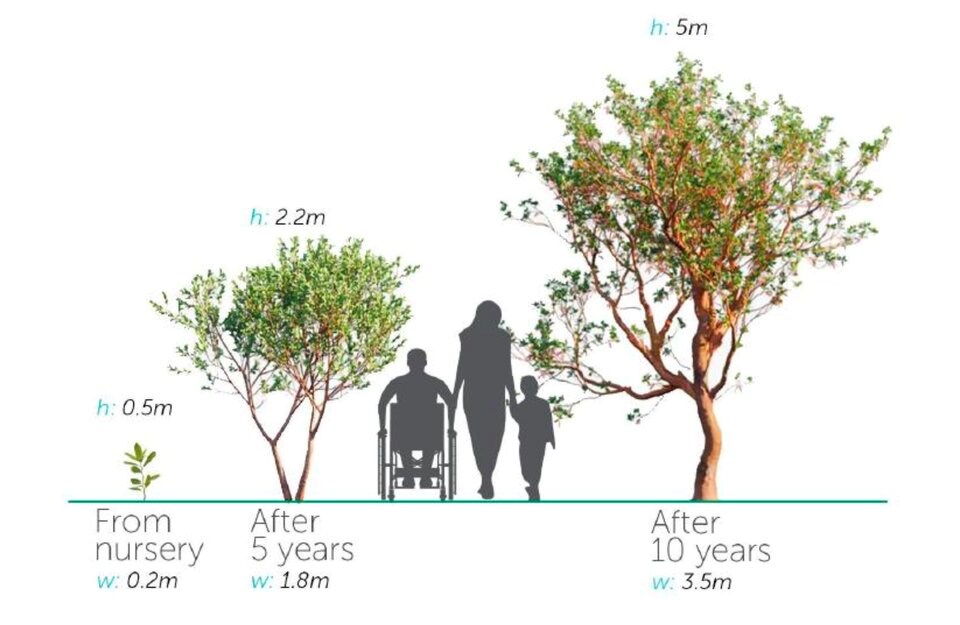

While a tree from the nursery might start small, it will grow and inevitably provide shade. In neighbourhoods with dense tree cover, carried out in Vancouver suggests that a pedestrian standing directly under a tree canopy would experience temperature reductions upwards of 17 C.

Planting a tree, said Herrington, “can actually reduce the cost of cooling and heating your house.”

Outside of a home’s backyard, trees can stabilize shorelines, reduce erosions, improve air quality and suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Trees can also be the centre of attention.

“Trees change over time. They can spark curiosity and wonder in kids,” Herrington said. “When you plant together, it can bring people together.”

Focus on children's play areas

The shade and cooling effects trees provide is especially important for children under five.

At this age, children struggle to regulate their body temperature in warm environments. That’s partly because they produce more heat for their weight and have faster rising core temperatures. It’s also due to the fact young kids are less efficient at cooling themselves because they sweat less than adults.

A 2020 Standards Council of Canada analyzing how Canadian communities tended to plan for heat safety on playgrounds, found a strong consensus among 55 surveyed experts that thermal comfort and shade has not been prioritized.

“Playgrounds often present some of the highest surface temperatures within an urban area, amplifying heat extremes — and most playgrounds lack adequate shade,” the report found.

That increased temperature of poorly shaded public spaces can contribute to a spiralling list of heat illness symptoms — and even death.

Long-term, sun exposure early in life is another big risk. Skin cancer represents one in every three cancer diagnoses in Canada. And about 90 per cent of those diagnoses are traced back to long-term sun exposure.

The Canadian Cancer Society estimates children who are burned by the sun five or more times double their chances of melanoma later in life.

Shade any way you can

Breann Corcoran has spent years researching how shade and ultraviolet protection can impact the quality of outdoor play. Now an environmental health and knowledge translator at the С����Ƶ Centre for Disease Control, she said prioritizing natural shade is good but is not always the best solution.

“A dense tree canopy can offer up to 90 per cent protection from UV radiation,” she said. “But not all shade is created equal.”

When Corcoran carried out a in eight YMCA child-care facilities across Vancouver in 2021, she found shade sails cut UV radiation exposure in half.

In another unpublished study, the researcher said children reported a 20 per cent improvement in thermal comfort while playing outdoors under shade.

“There's a place for built shade too, and it can be really effective,” said Corcoran.

She suggested people look to the lookbook's long list of artificial shade recommendations from gazebos to collapsible tents, to adjustable awnings, louvres and DIY fence coverings.

Such artificial shade structures are sometimes the only option, especially when waiting for trees to grow. With enough time, however, Corcoran said it’s hard to compete with nature.

“Being around trees is just healthy,” she said.

Don't forget to dapple

One big benefit of natural shade is the filtering effect it has on sunlight. Known as dappled light, the patches of light and shadow cast through a tree onto the ground have been found to have a soothing effect that leads to mental restoration, said Herrington.

“When the wind blows it creates a buoyancy, this very nice atmosphere of movement. Everything feels alive,” she said.

Studies in Australia have found trees that provide 60 to 90 per cent shade offer the best balance between protection from the sun and an attractive area to relax or play.

To come up with their list of top shading shrubs and plants for С����Ƶ residents, Herrington and her colleagues duplicated the Australian studies, while prioritizing native and fire-resistant varieties.

Starting with almost 100 species, the team quickly whittled down the list. Some plants had toxic parts or were considered invasive; others weren’t predicted to survive a heating climate.

As the list of species shortened, researchers placed a section of white cardboard in the shade of the plants and trees. Next, they took pictures of the dappled light as it danced across the surface. Those that performed best made it onto their list of the best 33 plants to provide high and medium shade across a variety of С����Ƶ microclimates.

“People tend to immediately go to the shade structure, which I can understand because it gives you immediate shade,” Herrington said.

Planting a tree, on the other hand, is valuing long-term goals over the immediate, she said.

Herrington’s suggestion: plant what works for your outdoor space, and then install of shade structure while you wait for it to grow.