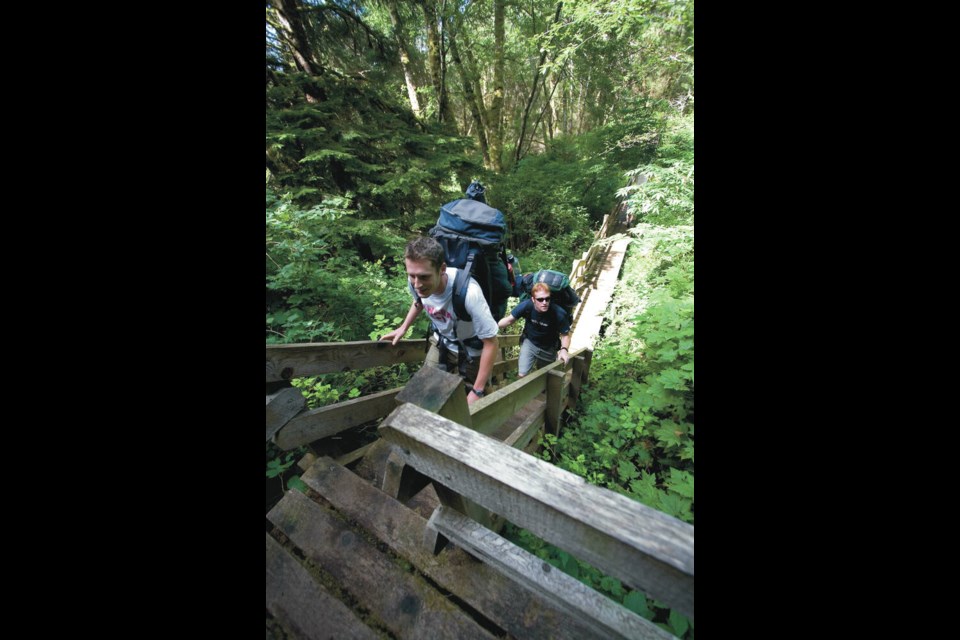

From sharing a ladder with a bear to a torrential downpour, Wayne Aitken has seen it all on the West Coast Trail.

Aitken, who co-wrote a guidebook for the trail with friend David Foster, has hiked the 75-kilometre stretch of coastline so many times he no longer knows the exact number.

“My usual response to that is more than 25 and less than 30,” he said.

A 39-year-old Aitken first hiked the trail in 1985 with his 15-year-old son and a work friend. They were ill-prepared and finished the five-night trip swearing they would never do it again, Aitken said.

But as time faded memories of the struggle, he recalled the trail as “one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been to,” he said.

So off he went to hike again every summer for the next three years, publishing the guidebook Blisters and Bliss: A Trekker’s Guide to the West Coast Trail in 1989.

Some of his favourite memories include the time he started climbing a ladder and looked up to see a black bear clambering down. “We got the heck out of there,” he said.

On another trip, unrelenting rain that soaked their gear forced his group to turn back and bail off trail. The day after he returned home, he was still wringing water out of his sleeping bag.

While Aitken’s favourite itinerary is seven nights and eight days, there are some who prefer running the whole thing in one go. John McKay was part of a group that in 1984 ran from Port Renfrew to Bamfield in 14 hours, carrying a fanny pack full of snacks and drinking water straight from the streams they passed.

“I had a good sleep that night. No doubt about it,” said McKay, a former long-distance runner.

Craig Hooper hiked the West Coast Trail before it officially opened as a recreational trail. He’s not sure of the exact year, but believes it was 1970. He saw just one other person in 10 days. Parts of the trail were so overgrown, he was walking waist-deep in salal and could only tell if he was following the path by sweeping his feet to see where the ground was cleared.

The only infrastructure at the time were rickety suspension bridges with signs warning people to use them at their own risk. He had to decide between climbing down a rocky gorge and back up the other side or risking the bridge. Hooper remembers sitting on the trail and agonizing over the decision, before walking the bridges.

“I took a chance on the bridge, envisioning myself plummeting to the bottom with my pack. I’m still here, so I guess it all worked out,” he said.

Their tales are just the kind of West Coast Trail stories the Maritime Museum of 小蓝视频 is seeking for an upcoming tracing its origins from a life-saving route for shipwrecked souls to a hiking trail that draws travellers from around the world.

The museum is asking people who have hiked all or part of the trail to submit written stories up to 500 words, photo-based stories with captions for context, personal objects loaned to the museum or short quotes about the experience.

can be sent to Heather Feeney, collections and exhibits manager at [email protected] until Feb. 29 and may be included in the exhibit No Walk in the Woods: The History of the West Coast Trail, which runs April 11 to Oct. 26.

Feeney said the museum heard from many hikers in the first day it opened for submissions, with people getting in touch to say they want to share photos and videos and loan paintings to the museum. One person has said they want to share their old hiking boots that have traversed the trail twice.

Feeney heard from someone who has hiked the trail 26 times and another who hiked in 1974.

The West Coast Trail is part of ancient paths and paddling routes used by First Nations for travel and trade. It passes through the territories of the Huuay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht First Nations. Their villages and camps were established before foreign ships arrived on the coast about 200 years ago. The coastline became known as the “Graveyard of the Pacific” as the number of shipwrecks in the Juan de Fuca Strait increased with growing marine traffic.

A life-saving trail was created with several stations, shelters and a lighthouse after the 1906 sinking of the steamship Valencia, which claimed 125 lives.

Pacific Rim National Park Reserve was created in 1970, and the West Coast Trail opened as a recreational hiking trail in 1973. More than 7,500 backpackers walk the trail each year, according to Parks Canada.

Permits to hike the world-famous trail are among the most highly coveted Parks Canada experiences, said Jennifer Dubois, visitor experience manager for Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. The trail is jointly managed by Parks Canada and guardians from the Huuay-aht, Ditidaht and Pacheedaht First Nations.

When reservations opened on Jan. 22 at 8 a.m., more than 6,600 people were in the online waiting room hoping to snag a permit, Dubois said. On that first day, 2,287 reservations were made, four per cent more than the opening day last year and 10 per cent more than 2022. For the best chance at getting a permit, prospective hikers should try when reservations open. Very few dates are still available nearly two weeks later, Dubois said, but cancellations can open up more spots.

The trail is open from May 1 to Sept. 30, and reservations are mandatory.

About one in 75 hikers will require a rescue effort from the remote trail due to slips and falls, pre-existing medical conditions or other concerns, Dubois said.

It’s important that hikers familiarize themselves with the , bring the appropriate gear, train and be willing to turn back if continuing is unsafe, she said.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]