Last month will go down as the hottest August in Earth’s 174-year climate record, in no small part to record temperatures on –°¿∂ ”∆µ's coast, according to satellite data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

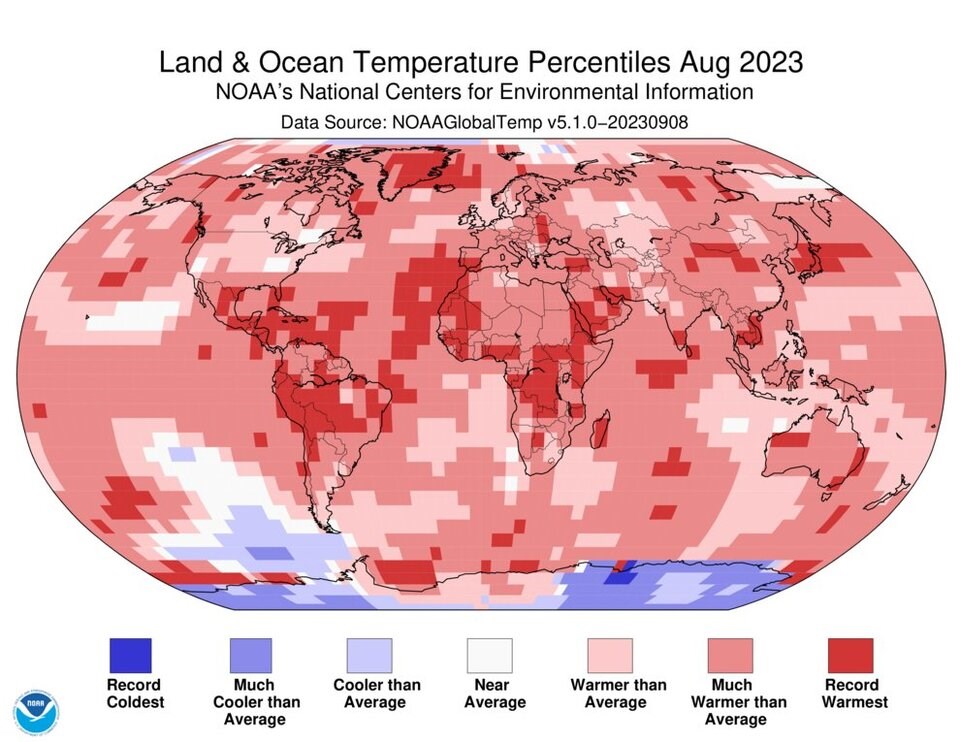

NOAA’s analysis found four continents — Africa, Asia, North and South America — had their hottest August ever. August also marks the fifth consecutive month global ocean surface temperatures have reached a record high.

The Arctic saw its warmest August and warmest summer on record, and at the planet’s other pole, last month was the fourth in a row where Antarctic sea ice hit a record low.

“Global marine heat waves and a growing El Niño are driving additional warming this year, but as long as emissions continue driving a steady march of background warming, we expect further records to be broken in the years to come,” NOAA chief scientist Sarah Kapnick said in a statement.

The agency found record-warm temperatures covered almost 13 per cent of the world's surface in August, the most since the start of records. Temperatures have now exceeded the 20th century average for 534 consecutive months in a row.

Some areas were hotter than others. Record temperatures were recorded in large swathes of Greenland, Japan, South America, the Caribbean, as well as West, Central and East Africa.

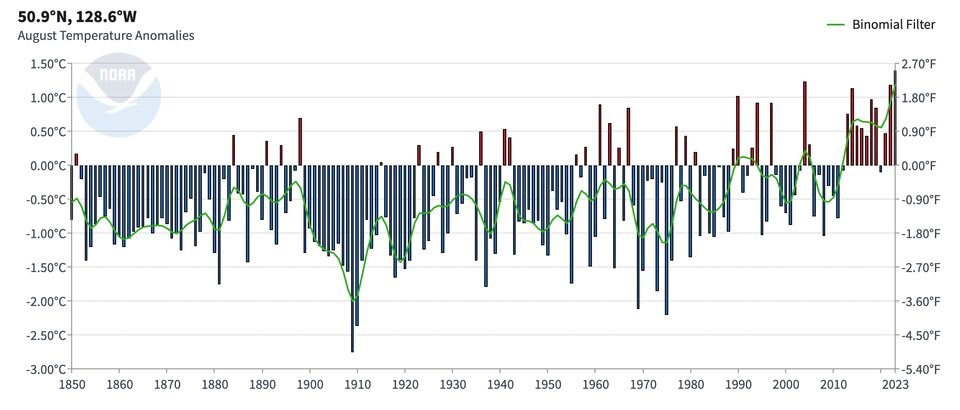

–°¿∂ ”∆µ coast sees August record temperatures going back to 1850

Most of Canada saw much warmer than average temperatures, including a large section of coastal British Columbia, which saw surface temperatures climb to their highest level ever.

The swath of record temperatures off North America's west coast extended in a grid stretching from the U.S. Pacific Northwest coast, through the northern half of Vancouver Island and up the –°¿∂ ”∆µ coast toward the Alaskan Panhandle.

About 10 kilometres off the coast of Tofino and off the northern tip of Vancouver Island near the Scott Islands, for example, temperature records going back to 1850 show surface temperatures in August 2023 were the hottest measured yet.

Off the coast of downtown Victoria, however, last month was beat out by soaring temperatures in August 2022.

Ellen Bartow-Gillies, a climate scientist at NOAA and lead author of its global monthly climate report, said that while not every location in the “record warmest” grid category will register as a record, enough did to trigger a global signal throughout a massive section of –°¿∂ ”∆µ coast.

“It’s definitely something that's notable on even the global scale,” said Bartow-Gillies.

“That has implications for the ocean because marine life is obviously affected by elevated surface temperatures.”

With 71 per cent of the Earth covered by ocean, when it warms, it feeds extreme weather systems, such as hurricanes, atmospheric rivers and the kind of storms that have unleashed powerful flooding across the Mediterranean in recent weeks.

“We might see shifts in fish population, and warmer oceans can also lead to sea level rise through the process of thermal expansion,” Bartow-Gillies said.

El Niño remains a wildcard

The warming trend is only expected to continue with the growing influence of El Niño.

La Niña and El Niño are used to describe warm and cool phases of a climate pattern that shifts across the tropical Pacific every three to seven years. As sea surface temperatures swing back and forth between Australia and South America, the cyclical El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon causes knock-on effects that disrupt temperature and precipitation patterns thousands of kilometres away — often in somewhat predictable ways.

In –°¿∂ ”∆µ, a cycle dominated by an El Niño pattern tends to deliver warmer winters, while La Niña brings colder temperatures.

The world is currently entering another El Niño event, but those warming effects don’t tend to fully affect the Northern Hemisphere until the winter after it emerges in the South Pacific.

“We’re heading into this El Niño season, and we're already breaking ocean heat record,” said Bartow-Gillies. “We're already seeing this really, really unprecedented heat in the oceans and you know, that's not going anywhere. That heat is here to stay.”

Bartow-Gillies says part of the explanation may be that La Niña’s global cooling effect over the past three years may have dampened the impacts of human-caused climate change.

“We don’t know the extent that climate is kind of bouncing back from that event versus how much of the current El Niño is affecting our climate” she said.

“It’s something we’re keeping an eye on. It's somewhat of a cause for concern.”

At the global scale, the climate scientist says there’s now a 95 per cent chance 2023 will be among the top two hottest years on record, up from 47 per cent last month.

“I hope people start to pay attention. This unprecedented heat is becoming more and more precedented,” she said. “A lot of the places around the world are not equipped to deal with this sort of record heat. They need to sort of face the reality.”

“Because at the end of the day, we just want to make sure that people are safe and healthy. And as we approach a really, really warm world, that's getting harder and harder to do.”