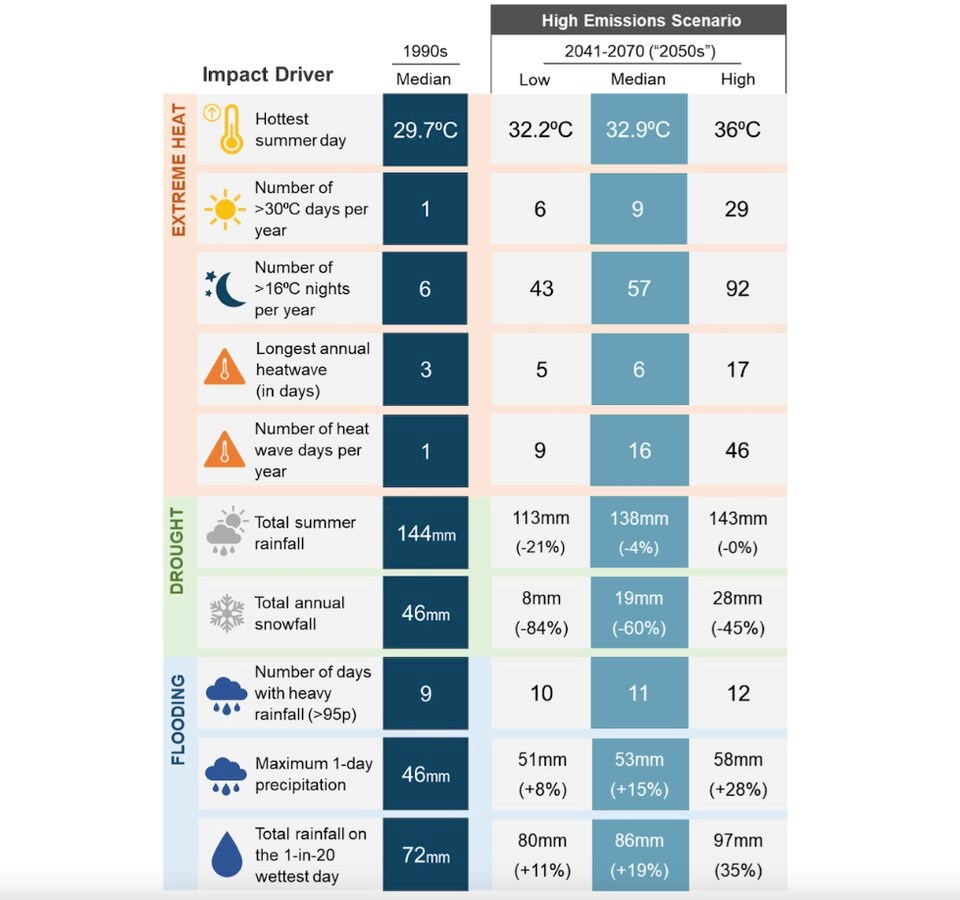

New climate projections for the City of Vancouver have found the number of days the city spends under a heat wave every summer could spike 16 fold compared to the 1990s if the world continues burning fossil fuels under a “business-as-usual” scenario.

The from the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium for the City of Vancouver offers an early look at how climate change will impact a big С����Ƶ city under three emission scenarios.

The findings, which have yet to be presented to Vancouver city council, found that by the 2050s, the number of extreme heat days above 30 degrees Celsius could climb to between six and 29 times higher. Hot nights above 16 C, meanwhile, are projected to climb to between 43 and 92 nights per year, up from an average of six hot nights a year in the 1990s.

A surge in extreme summer heat is expected to be accompanied by extended dry spells, spikes in fall rain, and a sharp decline in snowfall over the coming decades.

Armel Castellan, a warning preparedness meteorologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada who was not involved in producing the report, described the projected rise in tropical nights and extreme heat days as “astronomical.” That deadly combination is especially concerning, he said, for a city that hasn't been built to routinely deal with temperatures over 30 C.

“It is dangerous,” Castallan said. “We are shifting the baseline significantly.”

“We're going towards a different climate.”

Three climate futures

This is the first time Vancouver has ever received local-scale modelling under multiple scenarios — a format adopted by the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and considered the gold standard of climate science.

The report is based off nine global climate models down-scaled to within several city blocks. The researchers then used the models to forecast three climate futures.

Under a low-carbon scenario, green technology leads to steep reduction in emissions. A medium emissions pathway is where some progress is made switching from fossil fuels to green energy.

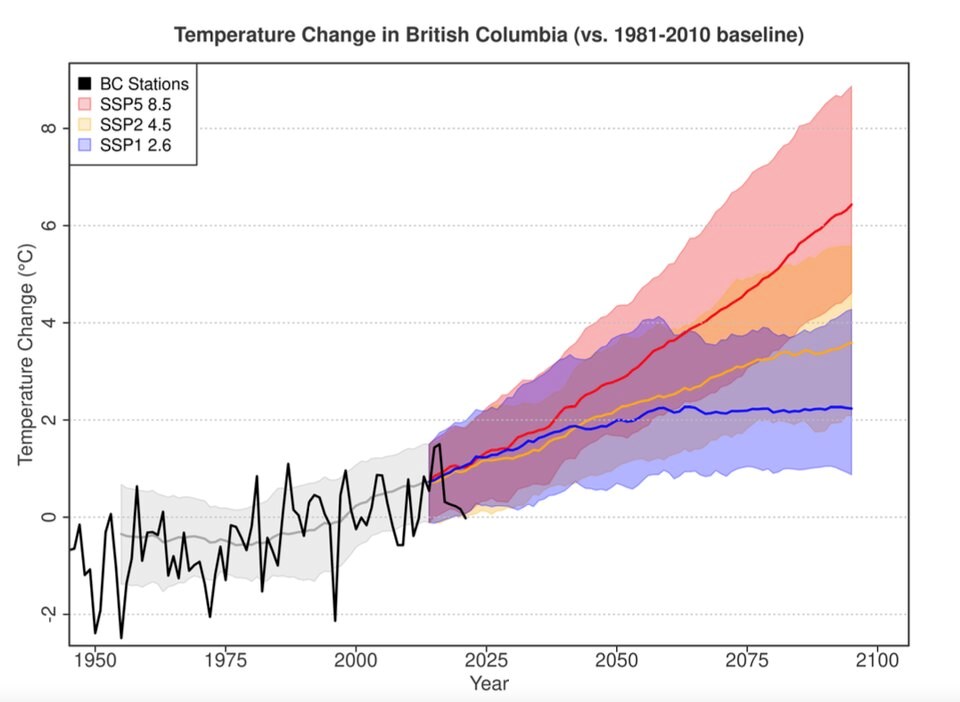

A high-emissions scenario, on the other hand, is a future trajectory where humans continue to release emissions through the continued and expanded use of fossil fuels. In this worst-case scenario — an option the City of Vancouver says it’s planning for — by the 2090s, global mean surface air temperature is expected to hit 4.3 C higher than the average between 1850 and 1900.

Described as a “stepping stone” to help the City of Vancouver plan for a warming climate, the report says that since 1950, air temperature in the surrounding Lower Fraser Valley has already seen an “clearly increasing trend,” warming as much as 0.42 C per decade.

In the past, average daily temperatures would hit an extreme average of 33.3 C once every 20 years. But by the 2050s, the report projects that same event could happen about once every two years, while at the same time growing almost 4 C hotter.

Rachel Telling, Vancouver’s acting manager of climate adaptation and equity, said those extremes caught her by surprise.

“That's a huge increase,” she said.

The extreme temperatures in the report represent average highs in average years. But some extreme temperatures — such as the 2021 heat dome that killed 619 people in С����Ƶ — are harder to model and will almost certainly be hotter, warned Nathan Gillett, a research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada who didn't work on the report.

“You do still get these more extreme events,” he said.

Mechanical heating demand to increase eight fold

The report warns Vancouver residents will need to adapt to more frequent, longer and more intense future heat waves, and that “public information campaigns linked to meteorological forecasts will be essential.”

“Health care and emergency services will need to be properly resourced to handle increased incidence of heat-related illness, stress and anxiety,” add the authors.

By the 2050s, the number of days that will require mechanical cooling in the city is expected to increase by a factor of 4.6; and by the the 2080s, that number climbs eight times higher than in Vancouver’s recent past.

That means old buildings will need to be retrofitted and new buildings will need to be re-designed to meet “a large projected increase in cooling demand,” the report notes.

The increased summer temperatures are expected to lead to higher rates of evaporation. Summer rainfall, meanwhile, is projected to drop 16 per cent by the 2080s. Under a high-emissions scenario, summer dry spells would last 17 per cent longer on average, “increasing the probability of drought conditions” and raising the likelihood the city would need to take more drastic steps to protect its water supply.

Snowfall to drop 60%

During the winter, the climate projections show the average amount of snow falling on Vancouver could drop 60 per cent by the 2050s.

“Obviously, that has impacts for winter recreation, but it also has huge impacts for our water supply system and drought,” Telling said.

The three reservoirs feeding Metro Vancouver’s regional water system are expected to see similar shifts in winter temperatures. That could impact the amount of high-elevation snow available to recharge reservoirs, the report says. Snowpack, warn the authors, “should be closely monitored.”

While overall snowfall is expected to drop, it’s not expected to free up municipal snow clearing budgets anytime soon. That’s because limits in the climate modelling make rare but sometimes heavy future snow storms in southwest С����Ƶ hard to capture.

“For this reason, it would likely be premature to make changes to municipal snow removal plans, for example, until at least mid-century,” the reports authors state.

Rain shifts to fall as frost comes to an end

The report found that under “increasingly rare” freezing temperatures, Vancouver’s spring and fall are expected to increase in length, effectively shrinking the winter season.

By the 2050s, Vancouver’s growing season is expected to extend a month longer; and by the 2080s, Vancouver is forecast to be “effectively frost free” with a growing season that lasts year round, the report says.

As temperatures warm year round, rain is expected to fall in bursts at certain times of the year.

Both single-day extreme rain events and total rainfall during Vancouver’s autumn season are expected to surge about 20 per cent by the 2080s.

“By the end of the century, some years may have more rain in autumn than in winter,” the report’s authors warn.

“Designers of urban drainage systems will need to plan for higher single- and multi-day rainfall amounts, with appropriate changes to culverts, storm drains, and other infrastructure elements.”

Brent Ward, the co-director of Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Natural Hazards Research, said the shift in temperature and precipitation patterns will likely have cascading effects on surrounding farmland.

“That’s going to impact food production. That’s going to make us more vulnerable. We do produce a lot of fruit and veggies here,” said Ward, pointing to the Fraser Valley.

Climate projections part of Vancouver's evolving adaptation plan

Telling said city staff have incorporated the report’s findings into the city's updated climate adaptation strategy, set to be presented to Vancouver city council in the coming weeks.

There are about 60 target areas in that plan spread out over five hazards — extreme heat, air quality from wildfire smoke, extreme rainfall, sea level rise, and drought. About 40 per cent of those offer new solutions never seen by the public, Telling said.

“It’s a risk-based action plan that looks at like, what are our highest risks, who in our city is at highest risk, and then tries to take actions to address that,” Telling said.

Some of those actions include piloting the planting of new kinds of tree seedlings better adapted to Vancouver’s future climate, and rolling out a resident adopt-a-tree program where people can care for street trees, added Telling.

Past research has shown urban canopies can reduce ambient temperatures by more than seven degrees Celsius in urban environments. That can save lives, experts say.

During Vancouver's 2021 record heat wave, a Glacier Media found emergency room visits due to heat illness were highest in neighbourhoods with the fewest trees, hottest temperatures and most marginalized people.

Since then, both the city and province of С����Ƶ have tried to close gaps separating more affluent tree-rich neighbourhoods with those most .

As part of a wider strategy to reduce extreme heat risk across the city, Telling said Vancouver city staff are upping the number of trees it plants, incentivizing the installation of cooling heat pumps, and launching a transportation pilot — effectively a taxi service to help people access cooling centres.

The plan is also about saving municipal money. At the federal level, the latest climate adaptation plan estimates that every dollar invested in climate adaptation measures can avoid between $13 and $15 in future costs.

“We want to know, like specifically for Vancouver, what is that number? What does that look like? And what are the benefits financially… on the health-care system or on our environmental spaces?” Telling said.

None of that is possible without an accurate picture of future risk. That’s where the latest climate projections come in.

A new window into the local impacts of climate change

Gillet said Vancouver’s city-level analysis would likely become an important window into the future as other towns and cities try to make sense of how climate change will impact them at a local level.

But analyzing future climates using city boundaries also has its limits. The report recommends expanding the Vancouver study to the North Shore mountains and the Fraser Valley to understand the links between the region's drier summers, winter snowpack and spring flooding.

Castellan said that some cities in the Metro Vancouver area close to the ocean will benefit from its cooling effects — “Mother Nature’s air conditioning,” as he put it. Communities built near unstable hill slopes might face more flood-induced landslides. Others, wildfire risk or flooding from nearby rivers. In short, local geography and urban design can have a big impact, Castellan said.

“Fractions of a degree matter in a big way,” said the warning preparedness meteorologist.

Wherever Vancouver's future climate ends up, many of the projected changes are already underway, and current data “indicate this trend will continue without significant cuts in carbon emissions,” the report notes.

For Tim Takaro, a physician and professor emeritus studying the health effects of climate change at SFU, the stakes presented in the report are high, and offer a striking picture of a “big public health risk.”

“I just hope people start paying attention to the urgency that reports like this portend,” said Takaro.

“We’re building [fossil fuel infrastructure] like crazy. We’re pretending like it’s OK. It’s not. It’s criminal. Because we’re pushing it onto future generations who have no say.”