Kathie Rennie remembers the snow turning to rain somewhere around Cache Creek, near the turnoff from Highway 97 to Highway 99.

A road-crew operator from Maple Ridge, she had always hated taking Highway 99 home from her cabin at Green Lake, near 70 Mile House. She never trusted that enough work had been done to keep the road clear and safe from falling debris.

On Monday, Nov. 15, 2021, however, she had few choices. A day earlier, a powerful storm system had arrived, triggering flooding that swallowed homes in communities like Abbotsford, Merritt and Princeton.

Over 17,000 people would soon be stranded or displaced, some escaping the rising water in trucks, RVs, jet boats and kayaks.

The floods and debris torrents crippled major roads and bridges, drowning huge swaths of the Trans-Canada Highway and largely cutting off land access between С����Ƶ’s coast and the rest of the country.

Rain or not, Rennie and her husband had to get to work, and their 10-year-old son had school. But there was only one way home — a mountainous corridor along Highway 99 known as the Duffey Lake Road that snaked its way through the towns of Lillooet and Pemberton to eventually reach Metro Vancouver.

“It was like, hey, well, let’s just give it a shot,” said Rennie. “We had no intention of stopping.”

The pile-driver

Steven Taylor hadn’t lived in С����Ƶ for long. The 53-year-old father had come west a year earlier to find work after a pandemic slowdown led to downsizing at the pile-driving company where he worked in Alberta.

Back in Calgary, Taylor was a fixture in the rugby community — “an aggressive individual” on the pitch, a “teddy bear” everywhere else, as best friend and best man Dean Hopkins described him.

Taylor began bouncing around work camps in С����Ƶ’s coastal mountains. Soon, his wife, Diane, had had enough of the long-distance relationship and moved to Surrey in order to be home when Taylor finished a job.

Taylor’s crew was supposed to be starting a new project when the weather came in. An unusually powerful atmospheric river had funnelled a long ribbon of water vapour from subtropical latitudes to С����Ƶ’s coast. The duration and intensity were unlike anything seen in decades. Over the space of 48 hours, more than 20 rainfall records fell across С����Ƶ

Taylor’s bosses closed the camp down. Taylor called Diane as he was leaving to say he was on his way back and would call when he had cell service again.

A romantic getaway

It was supposed to be a quick trip, a long-deserved weekend away.

A couple of days earlier, Anita and Mirsad Hadzic had left their two-year-old daughter with her grandmother in New Westminster. Their destination: the Sparkling Hill Resort on the north end of Okanagan Lake, a five-hour drive away.

Spas, hikes, yoga and a spectacular view of the Monashee Mountains — the resort offered the perfect getaway for two parents raising a toddler.

On Monday morning, Anita and Mirsad woke at 6 a.m. ready to go home. They checked the province’s online highway conditions portal, DriveС����Ƶ. The Coquihalla Highway, their planned route back to Vancouver, was closed due to flood damage.

There was only one road back: Highway 99. The couple called the grandmother and told her they were leaving early because it was going to take eight hours to get back to Vancouver.

A notice of civil claim later filed in С����Ƶ Supreme Court says that until at least 9 a.m. that day, “there was no mention of any natural disasters, warnings or alerts to warn drivers of hazardous road conditions along this highway.”

“The highway was shown as open and safe…”

Nov. 14 and 15 would prove to be the rainiest days on record for that area, with over 90 millimetres of precipitation accumulating in nearby Pemberton Valley. Yet at no time during those two days did the province carry out a geotechnical assessment in the area, according to a proposed class-action lawsuit that has not yet been certified. A certification hearing has been set for April.

'Felt like an earthquake'

By late morning, Rennie started seeing rocks “all across the road.”

With nowhere to turn, the family crept their Ford F-350 forward.

About 42 kilometres southwest of Lillooet, high above the highway, something much bigger was about to get in their way.

Taillights came into view. Something was blocking traffic. They got out and looked around the corner. A mudslide had thrown a massive field of debris in their path, blocking their last route home.

“There was no way we’d be able to drive over that. So we just parked in line with everybody else,” she said.

Within a few minutes, a bottleneck of traffic stretched behind them.

All hill slopes have a breaking point. Sometimes the trigger is an earthquake, a poorly planned building site or shock waves from blasting. Sometimes a fire that burns a hillside can raise the risk of a mudslide across an entire watershed. More often than not, all that’s required is gravity, a steep incline and the right amount of water.

In the fall of 2021, weeks of steady rain and warm temperatures had primed many mountainous areas across the province for slides. Rain and snowmelt had seeped into the spaces dividing dirt, rock and roots — slowly lubricating the earth.

Then the torrential rains came, pushing the soil’s friction to its limit. In an instant, the force of gravity overpowered the ability of innumerable hillsides to hold themselves together.

Untethered from the mountainside, morasses of soil and stone barrelled downhill at 30 to 60 kilometres per hour, ripping trees up by the roots, and often sending boulders into a “surge front” ahead of the mudslide.

In other parts of the province, at least 1,200 landslides combined with floods to wipe out 36 major sections of highway.

On the Duffey Lake Road, Rennie remembers feeling it before she could hear it. “It felt like an earthquake,” she said, a “huge rumble” and a symphony of trees snapping “like a million twigs.”

She stepped out of the truck into a scene of mayhem. Behind them, the line of traffic ended in a towering soup of mud, boulders and splintered trees. Roughly 50 vehicles were trapped between two mudslides.

People were screaming “Oh my God, we’re going to die,” recalled Rennie. Others ran down the road yelling into vehicles for anyone who knew first aid.

Rennie had studied to become a paramedic decades ago. She told her husband to stay in the truck with their son “no matter what” and climbed out. Slipping between cars, she found a handful of other people looking to help.

“There’s just a group of us that came together as leaders, so to speak,” said Rennie, pointing to a forester, a fireman and an officer in charge of inspecting commercial trucking. “We never even introduced ourselves.”

The debris field towering over her head settled and flattened down the road, Rennie said. She began directing vehicles out of the way. “We were afraid that it was going to start wiping out cars.”

A few minutes later, a horrible realization settled on them — there were people caught in the mudslide.

Two women and a dog climbed out of a half-buried vehicle. A man, later identified as 36-year-old Brett Diederichs, must have seen it or heard it coming, said Rennie.

“He was outside of the vehicle and shoved his mom in the vehicle [with his partner] and slammed the door,” said Rennie. “He was gone … they survived.”

Dozens of people trapped between the two slides grabbed shovels, tire irons and two-by-fours — anything they had in their car. They started digging.

Another two men were swept off the road by the torrent, their Jeep launched upside down into the upper branches of a tree. “That’s what saved them,” said Rennie.

Of the roughly 40 people now digging, some climbed to help the trapped men down from the tree. They guided survivors through the mud to where Rennie was waiting with a handful of warm vehicles, dry clothes and blankets. “All I’m trying to do is keep them out of shock,” she said.

She would ask one simple question: Is anyone you’re with still missing? Some said no. Others said yes.

Back in Calgary, Hopkins quickly learned from Taylor’s wife that his best friend was overdue. He started contacting all the restaurants, bars and hotels in the area — nothing.

“He always answered my phone calls. It was just pinging, pinging, pinging. No answer. No answer. No answer,” he said.

'Just start digging'

Some of the first outside help came by chance. Past the first slide, a snowplow operator had made contact by yelling across the divide.

Rennie says the older man was probably just checking higher-elevation roads for snow. With no one else there, the plow operator slowly started to cut a path through the mud.

But snowplows aren’t made for mudslides and if the machine broke, Rennie feared it could be hours until someone could get to them. “ ‘Just remain calm and do it at your own pace,’ ” Rennie remembers telling him.

In less than an hour, the plow had punched a narrow path through the rock, mud and trees that was just wide enough for a vehicle.

Those pulled alive from the mud were divided between a few vehicles. Rennie took the two men from the Jeep to the medical clinic in Pemberton, about an hour’s drive away. “I just said to everybody: ‘You’re not staying here, you’re not staying here,’ ” she said. “Nobody was left behind — other than the ones that were missing.”

Down the valley, the members of Pemberton Search and Rescue heard their pagers go off at 11:59 a.m. Within the hour, helicopters had landed the first of 22 rescuers who would eventually scour the scene over three days, according to SAR manager David MacKenzie.

On the north end of the slide, Max Paulhus and his team from the Lillooet and District Rescue Society jumped in their truck and sped down the highway. The team regularly carries out rescues in rapids, off the sides of cliffs, and on highways. When they arrived, RCMP units were already diverting traffic.

The rescue teams pulled out chainsaws, axes, shovels and pry bars — anything to get through the morass, said MacKenzie. “When we first get there, we’re not in a recovery mode. We’re still in a rescue mode,” he said.

Anyone not still trapped in the mud had left, and Paulhus remembers thinking the mountain could slide down again at any time. “One minute, I’m standing on a log; the next, I’m up to my waist in three feet of mud and rock,” he said. “You find a fender and you just start digging.”

The Jaws of Life was brought down the hill, a hydraulic rescue tool that can pry open roofs and doors like a giant can opener.

Paulhus remembers finding the first victim. And then another.

Over the coming days, rescuers would find the bodies of Taylor, the Hadzics and another 61-year-old man, who has not been publicly unidentified.

Diederichs’ remains have not been found.

The five slide victims would be the only ones directly killed by the natural disaster sweeping across the province. But soon, their deaths would be blamed on more than a force of nature.

A search for answers

In the days after the Duffey Lake Road landslide, geoscientist Pierre Friele got a call from a friend doing avalanche research near Pemberton. With so much destruction, did Friele, who researches landslides, need any aerial photos?

“I said: ‘Yeah, fly over that Duffey thing and take pictures for me,’ ” said Friele.

When the photographs came back, Friele saw evidence of human activity at the landslide’s source. He needed to get closer to be sure. But with a storm coming, Friele had to hurry before rain or snow erased the clues left behind.

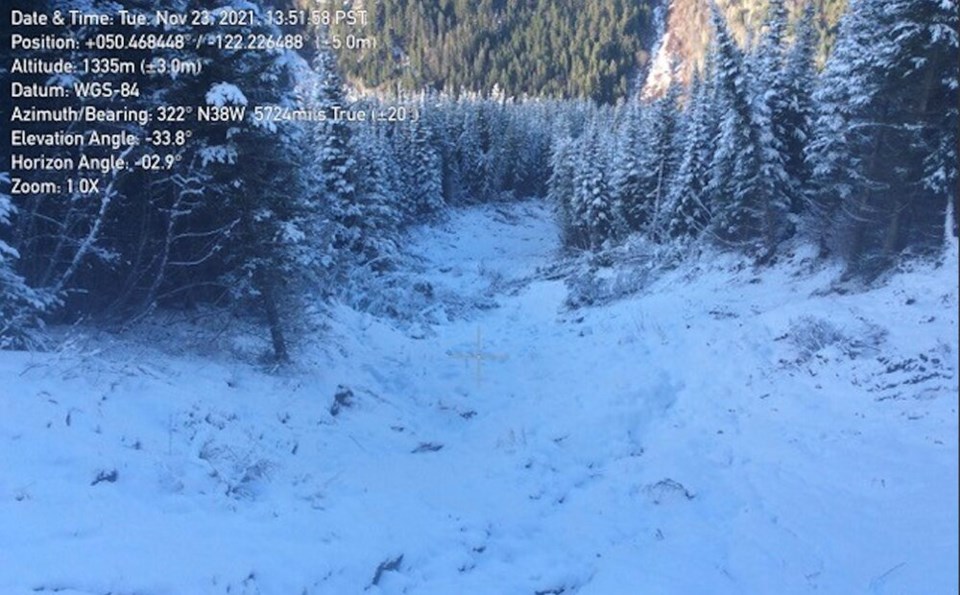

A few days after the atmospheric river hit, Friele hiked over hundreds of metres above the Duffey Lake Road landslides. In one photo, a freshly carved escarpment traces the line of the logging road; in another, a path of destruction has been blazed through the forest toward the highway.

Friele could see hundreds of metres of logging road. Built sometime between the 1970s and 1990s, the road had since suffered from decades of neglect, the geoscientist said. In one switchback where a culvert had never been removed, small slides had blocked the flow of water. Instead of draining where it should, the water spilled onto the logging road below and seeped into the steep ground.

Heavy with water, the hillside teetered, and on Nov. 15, reached a tipping point. “Nobody’s been paying attention,” Friele said.

The province used to pay attention, said the geoscientist. By the early 1990s, generations of logging across the province had left a vast network of back roads, many deemed to vastly increase the risk of flash flooding and landslides.

The NDP government of the day set out to deactivate many of them, ripping out culverts and bridges, and reforming the natural slopes they cut into. But in recent decades, that effort has stalled, and Friele says a large number of old logging roads have been left to sit, never deactivated.

“These roads that haven’t been decommissioned properly, they are vulnerable, and we will see landslides from them,” Friele said. “There is still quite a large number of roads out there that are in this condition.”

Disturbances from logging roads and wildfires are priming С����Ƶ’s forest slopes for failure, say experts. That’s compounded by human-caused climate change, which is expected to drive more frequent and intense rainfall during the province’s fall, winter and spring.

One 2020 study from a researcher at the University of Victoria-based Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium found climate change could increase the frequency of landslide hazards in С����Ƶ by a third by 2050. On the West Coast and in the northern Rocky Mountains, the number of days where hazardous landslides are a risk could climb by eight to 11 days per year.

On Vancouver’s North Shore, the destructive consequence of climate change could increase the risk of landslides by 400 per cent, according to a study produced last year by the late Vancouver geoscientist Matthias Jakob with BGC Engineering.

“It is sobering, but it falls in line with many other climate-change predictions. Predictions have, for most geophysical phenomena, become more dire, not less,” Jakob told the North Shore News just two weeks before the landslide hit Highway 99.

Jakob, who recently died in a paragliding accident, was set to testify as an expert witness in the proposed class-action lawsuit filed against the province last March, and set to be heard in court next spring. The Hadzics’ daughter is listed as the lead plaintiff.

Carie-Ann Lau, a senior geoscientist at BGC Engineering and Jakob’s close colleague, said she couldn’t speak directly about the Duffey Lake Road slide due to her firm’s involvement in the ongoing litigation.

Lau is currently investigating roughly 1,200 landslides she helped identify at some of the heaviest-hit bridges and highways in the Fraser Valley. So far, she says at least 10 have been linked to logging roads.

In one site near the Wahleach Falls Generating Station between Chilliwack and Hope, Lau says she found evidence logging roads had triggered landslides on multiple occasions — in the 1980s, 2017 and 2021.

“We’re playing catch up with almost 100 years of logging in some cases,” said Lau.

The proposed class-action lawsuit against the province and a road-maintenance company claims they should be held liable for not assessing Duffey Lake Road hazards — including risks posed by a logging road above the highway — at a time the corridor was being used to funnel traffic to the coast.

“If this [logging] road had been properly permanently deactivated, the potential for mudslides would have been detected and preventatives measures put in place,” the suit claims.

None of the claims have been tested before the courts. A spokesperson for the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure declined comment, as the case is before the courts.

While Lau wouldn’t comment on the Duffey Lake Road landslide, she says keeping tabs on dangerous hillsides is a growing problem across the province.

“We’ve got a lack of qualified professionals that are able to go systematically look at hundreds of sites and prioritize that risk,” said Lau, whose company is doing flood, landslide and debris-flow assessments for the province, First Nations, pipeline companies, railway operators, regional districts and municipalities.

“I haven’t stopped in 18 months, not since the fires in Lytton.”

How much and when money is made available is also a problem, she says. Historically, provincial or federal funding gets handed down after a disaster, and rarely at a scale to pay for quantifying and ranking all the infrastructure at risk across С����Ƶ

Lau says С����Ƶ is far behind countries like Switzerland or Japan, where on-the-ground science is being combined with big data to map out risk from landslides.

Friele agrees triaging С����Ƶ’s risk of landslides is feasible. “We know where all these roads are,” said Friele. “We have topographic information.”

He suggests combining that data to narrow down and stabilize hillslopes where old logging roads are most likely to trigger landslides near infrastructure and people.

“We don’t move until we’ve been kicked in the butt,” said Friele. “But I think this is clearly one of those events that’s going to drive some change.”

A year later, the lives of those lost at the Duffey Lake Road landslide continue to weigh heavily on family and friends. Hopkins says he has been in regular contact with Taylor’s wife, Diane, since that day. But in the lead-up to the anniversary, she has “gone dark.”

Those involved in the rescue, meanwhile, say the days of searching still haunt them even after multiple critical stress debriefings.

“It was a very hard thing to deal with,” said Paulhus. “You don’t really want to go home and tell your wife what you did. You can share some things — and some things, you can’t.”

With files from Brent Richter/North Shore News