As you read this you are almost certainly surrounded in a world of plastic.

Since the rise of petroleum-based polymers in the mid-1950s, the materials have become a ubiquitous stalwart of modern life — from the smart phone in your hand to the shoes on your feet.

But just as they have accumulated in our lives, they have penetrated almost every natural environment on Earth, tangling turtles, choking birds and littering our highest peaks.

Perhaps the most visual reminder of humanity’s plastic problem comes when our refuse whirls into giant trash vortexes in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Worse, the horrifying ecological spectacle hides the fact that 70 per cent of the plastic at sea sinks to the bottom as microscopic particles — fundamentally changing the makeup of ocean floors and beaches across the world.

If that wasn't bad enough, by 2060, humanity's consumption of plastics is projected to triple, while the volume that leaks into the environment is forecast to double to 44 million tonnes per year, according to the .

But what if things could be different? What if we had something that looked like plastic, behaved like plastic but is totally biodegradable?

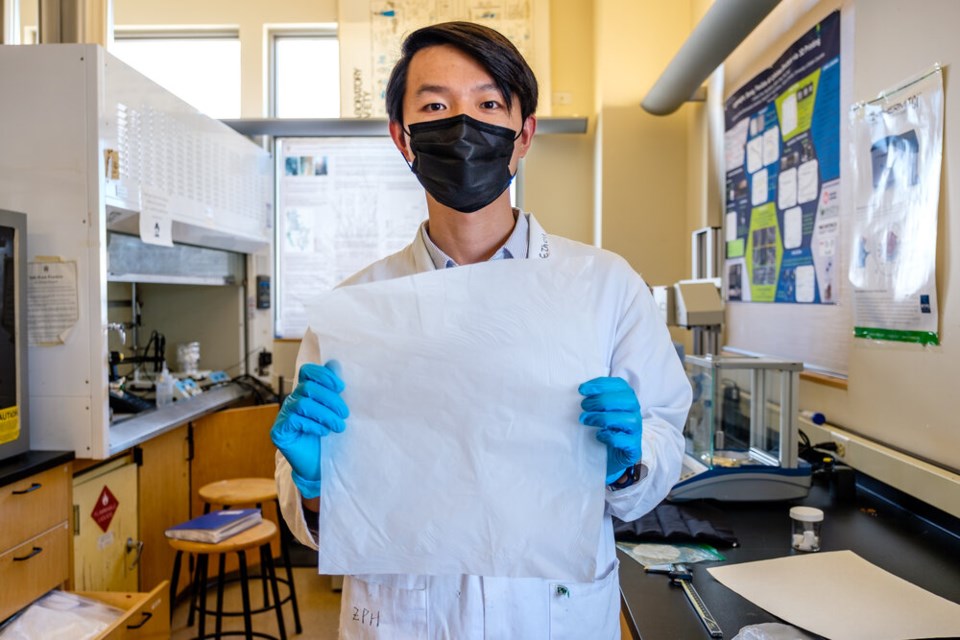

It’s a question that has kept University of British Columbia researcher Feng Jiang busy in recent years.

“It’s really an alarming crisis,” said Jiang in a recent interview with Glacier Media. “Less than 10 per cent of single-use plastics are recycled.”

An assistant professor in U小蓝视频’s Faculty of Forestry, Jiang has looked to the trees for answers.

How solving plastics could reduce wildfires

British Columbia’s forests are , a product of years of forestry practices and a wildfire regime that has largely favoured blanket suppression over .

As climate change drives drier summers, wildfire experts have warned of a coming “” unless something is done to commercialize the millions of tonnes of scrap wood waiting as kindling in 小蓝视频's forests.

“Post-harvesting, only about 50 per cent of the materials are used,” said Jiang. “Those branches and tops of trees will just get left in the forest. Over time, they’ll dry up and become fuel.”

“We’re trying to get that material and turn it into packaging, and at the same time trying to reduce the fire hazard in the forest.”

With funding from 小蓝视频’s Ministry of Forests, Jiang and his graduate students devised a way to distil cellulose from wood waste, though the researcher says hemp fibre and agriculture waste are also viable sources.

The process breaks down the wood fibre in a solution of cold sodium hydroxide. After mechanically blending it — Jiang’s method is the first to use small amounts of energy and chemicals — the sodium hydroxide is recycled for the next batch.

They then took that 100 per cent cellulose solution — a similar precursor to paper —and manufactured a transparent, biodegradable film.

The prototype material has similar properties to the plastic used in bubble wrap or envelopes in the mail. Like its plastic counterpart, it could also be formed into bags for coffee, cereal, chips, as well as frozen and fresh fruit or vegetables.

“We can print on it too. It will work for packaging snacks,” said Jiang.

Strong when wet, just toss it in the compost

To test its durability, the researchers soaked the film in water for over a month. When it came out, Jiang said “it was still mechanically strong.”

Jiang said they are still looking to add “stretchability” to the film so that it can carry more weight like a single-use shopping bag. They are also working to understand how the gases emitted by aging fresh vegetables might degrade the film.

The most important thing, he said, is that the plastic replacement film remains strong when needed and can still be thrown in the compost.

In one test, Jiang placed the film in soil for three weeks. At the end of the experiment, there were only a few small fragments left.

“The microbes in the soil would degrade it — just as they degrade vegetables, they can degrade this film,” he said.

Jiang says he’s speaking with plastic and paper manufacturers over the next few days to find a partner who can scale up production.

“The next goal is to make a roll of plastic. The bigger the better,” he said.

That way they can conduct larger-scale experiments. If all goes well, he says he could have a bag ready to go within a couple of months.

Jiang is acutely aware that the longer it takes to find a replacement to plastic, the more petroleum products will end up contaminating environments around the world.

Time, he said, is not something he wants to waste.

“The ultimate goal is trying to combat climate change,” Jiang said, “reducing petroleum use and slowing wildfires at the same time.”