Northwest С����Ƶ is frequently featured in travel magazines, touted as a place to visit before you die, in large part to see its abundant and varied wildlife. The region also faces increasing commercial and industrial ��development and natural resource extraction, which threatens species already struggling to survive.

The region is home to a dozen animals designated as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Species in Canada, an independent group of wildlife experts and scientists. The committee reports to Environment ��and Climate Change Canada, which decides if animals should be added to the official registry under the federal Species At Risk Act. Eight of ��those 12 animals have been officially designated under the act to date. Many more could end up on the list if the province continues to give the ��green light to projects that have the potential to impact their ��habitats.

According to the World Wildlife Fund’s , global populations of mammals, fish, birds, reptiles and amphibians have declined an average of 68 per cent between 1970 and 2016. This ��rapid loss of wildlife is often referred to as the sixth mass extinction event and the culprit, unlike the previous five, is us.

As human populations continue to grow and expand, critical habitat for animals is ��wiped out or fragmented, isolating populations into smaller and smaller ��groups. It’s getting busier in our oceans, as we import and export more ��products, and our seemingly insatiable consumption of natural resources ��means our forests, mountains and rivers are increasingly under threat. ��Industrial development sends greenhouse gas emissions into the ��atmosphere and contributes to climate change, which is wreaking havoc on ��animal species around the world.

“Having ��good biodiversity and good diversity within populations can help ��alleviate change,” Pippa Shepherd, a species conservation and management ��ecosystem scientist with Parks Canada and a member of the committee, said in an interview. “You want diversity within a species and the diversity that exists among species, obviously, to be able to respond to��what is put in front of them.”

Chris Johnson, also a member of the committee and a professor of ecosystem science at the University of Northern British Columbia, said a lot of good conservation work has been done in the province, but getting the wheels in motion to protect a species can take years.

“For me, a big priority is to see species at risk legislation in С����Ƶ,” he said in an interview. “The federal act only applies to species that are found across Canada and to be honest if a species was really abundant in another province and was at risk in С����Ƶ, it probably wouldn’t be assessed simply because nationally it’s doing okay.”

Meet the ��eight officially endangered animals — and one familiar species in dire ��straits — relying on what remains of northwest С����Ƶ landscapes for their ��survival.

Black swift

The black swift is a small bird that nests in caves and on rocky coastal cliffs, ��often setting up shop behind waterfalls to avoid predation. According to ��its description on the federal species at risk registry, the black ��swift could be profoundly impacted by climate change as decreases in the ��annual snowpack and glacial melt cause those sheltered sites to dry up ��and become exposed.

The bird ��is fast and acrobatic and feeds while flying. The swift’s diet consists ��of flying insects such as wasps, flies and beetles, as well as spiders��that catch rides on air currents. Conservative estimates suggest 10 per cent of insect populations worldwide are at risk of extinction, and this decline threatens the bird’s survival.��

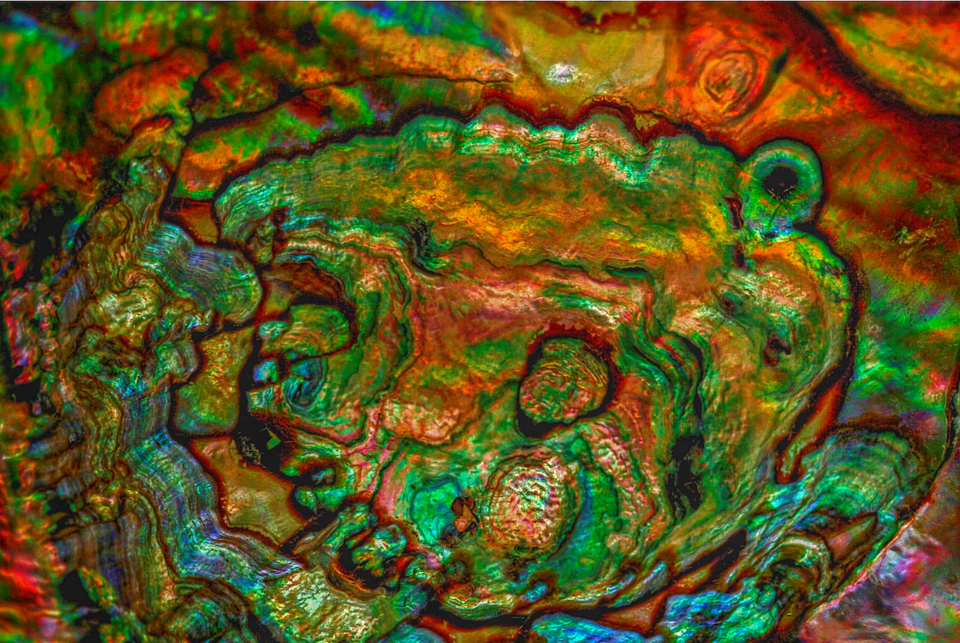

Northern abalone

This shellfish was once an important food source for First Nations along ��С����Ƶ’s coast, and the iridescent shells were used in ceremonial regalia. In the 1970s and 1980s, the abalone commercial fishery nearly wiped out ��the species, which has continued to decline despite a complete closure ��of the fishery in the 1990s. According to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, ��less than one per cent of abalone spawn survive to adulthood and because ��adults gather to breed, they are highly susceptible to poaching. Like��other filter-feeding shellfish, they are also extremely sensitive to environmental changes and pollutants.��

In an ��effort to save the species, several First Nations in the region have ��been working to educate the public, prevent poaching and rebuild��populations.

Blue whale

As the largest animal on the planet, the blue whale is an iconic species. It ��was hunted to near extinction in the first half of the 20th century, and��the population was fragmented into three subpopulations — Antarctic, ��Atlantic and Pacific. The Pacific population that travels along С����Ƶ’s ��north coast and into Alaska waters has fewer than 250 individuals.

Ship collisions are among the greatest threats to the species. ��As international trade continues to grow, more high-speed container ��ships are traversing the Pacific Ocean. Many ship strikes likely go ��unreported, or even unnoticed, and because blue whales typically sink ��when they die, it’s hard to gather accurate data. The International Whaling Commission is developing a database of known ship strikes to identify “hot spots” where whales congregate near shipping routes so ships can avoid them.

Like all whale species, the blue whale is at risk of entanglement in marine debris, such as abandoned or lost fishing gear. But scientists think blue whales can usually break free from most entanglements because of their size.

The blue whale feeds on krill by gulping vast amounts of water containing the ��tiny creatures and then pushing the water out through its baleen, leaving the food behind. This process also leaves behind microplastics. While the effects of ingesting microplastics are still not fully understood, potential impacts could include lower ��reproductive rates, decreased immune system function and increased vulnerability to diseases.��

Little brown myotis and northern myotis

The little brown myotis is the most common and abundant bat species in Canada. ��Known to roost in buildings and forage near human habitation, the bat is��familiar to most people in northwest С����Ƶ Its cousin, the northern ��myotis, or northern long-eared bat, prefers old-growth forests for its��habitat and hibernates in caves, mines and tunnels.

Northwest ��С����Ƶ populations of these bats may represent a last stand of sorts, as ��both species succumb to white nose syndrome, a fungal disease from an ��invasive pathogen that is spreading rapidly across North America. At ��least seven provinces and 35 states have reported outbreaks, including С����Ƶ’s neighbour to the south, Washington. ��This is a big deal because eastern colonies have already lost 94 per cent of their population to the disease, which attacks the bats in hibernation.

Losing an ��animal that can eat over 1,000 insects an hour — including mosquitoes — ��would not only transform the ecological landscape but also the ��socioeconomic landscape. A U.S. study on the economic importance of bats as natural pest control in agricultural settings estimated losses of at��least US$3.7 billion — and that doesn’t include downstream costs as crops are sprayed with more pesticides and humans ingest those ��chemicals.

Basking shark

Basking sharks are the second-largest fish species in the world. Slow-moving ��filter-feeders, they can reach up to 12 metres long and 5,200 kilograms, ��which is just shy of the average weight of an African elephant.

Historically,��the sharks would gather in groups of up to 1,000 off С����Ƶ’s west coast. ��Once considered a nuisance by Pacific fishers plying their trade in ��those same waters, basking sharks were the target of eradication efforts��by the federal government from the 1940s to 1960s. According to the Fisheries and Oceans Canada recovery plan for the species, only 37 basking sharks were spotted in С����Ƶ waters between 1996 and 2018.

The ��biggest threats facing these creatures are entanglements with marine ��debris and collisions with ships. Unlike blue whales, basking sharks, big as they are, don’t have the girth to free themselves from fishing��gear.

The ��species is slow to reproduce — females can take up to 20 years to reach ��maturity — which means the sharks need help now to avoid extinction. To ��that end, collaborations between government authorities, environmental ��organizations and scientists are underway. Janine Malikian, a ��communications adviser with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, told The ��Narwhal in an email that С����Ƶ residents can help.

“The public can play an important role in helping the population recover by reporting any possible sightings of basking sharks and providing photographs to verify sightings.”

North Pacific right whale

The North Pacific right whale is one of three distinct right whale subspecies. Its population is in the hundreds and some subpopulations may be under 50 ��animals. While some of these subpopulations may still travel through��northwest С����Ƶ waters, the last whale seen here was in 1970. There have ��been a handful of unconfirmed sightings since, but this population is on��the brink of extinction.

North Pacific right whales were once abundant along the west coast of North��America, in the waters around Hawaii, off the coast of Japan and in the ��Arctic waters of Alaska and eastern Russia. Starting in the mid-1800s, right whales were hunted to near extinction. Despite a 1937 ban on the ��commercial harvest of right whales by the International Convention for��the Regulation of Whaling, illegal whaling of the species continued until the 1960s.

In 2004, researchers identified a group of 23 animals — including two calves — in ��the Bering Sea. No right whale vocalizations were heard during acoustic surveys conducted in the late 2000s off С����Ƶ’s coast.

Sei whale

Sei whales are the third-largest whale species and, according to the International ��Whaling Commission, the least understood. Like many cetacean species, sei whales were hunted to near extinction during the heyday of commercial whaling in the Pacific in the 1950s and 1960s. There are ��fewer than 250 individuals that frequent Canadian waters. While there is ��an international ban on commercial whaling of the species, Japanese whalers still kill up to 134 sei whales every year under Japan’s scientific whaling program.

The Canadian government, in its conservation studies of the species, noted the danger of increasing shipping traffic from Kitimat as LNG projects are completed. Based on historical data, the report said the shipping ��routes from Kitimat likely cross critical sei whale habitat and ��highlighted spills and ship strikes as the main threats to the species’ survival.

Sockeye salmon

Sockeye salmon are not officially endangered, but some populations have already gone extinct and some subpopulations are under consideration for��designation on the federal registry. Many for at least 70 years.

SkeenaWild science director and PhD candidate at Simon Fraser University Michael Price said in an interview the call for salmon conservation has been��ongoing for a century. “Alarms have been sounded decade after decade for��100 years.”

In��northwest С����Ƶ, endangered populations include the Bowron, Takla-Trembleur and Quesnel. Both the Bowron and Takla have seen steady ��declines for years, but the annual catch of the fish has remained high. ��Marine and freshwater habitats are continually under pressure from ports ��and marine export terminals, mines and forestry. The Quesnel population��faces all those threats as well, but has the added potential threat of pollutants from the Mount Polley tailings dam failure.

Price said he’s often asked if he thinks sockeye will become extinct. “At a ��species level, no, I think they will persist. They’ve persisted for more than a million years, and look what they’ve gone through.”

But he said the implications of losing a spawning population are complex. He��noted that direct consumers of the fish like bears and wolves rely on salmon returns in multiple areas for sustenance. One population in a creek or river might provide a food source for two weeks and once that’s gone, those animals will put higher pressure on other tributaries. But ��it’s the loss of biodiversity in the ecosystem that has far-reaching effects.

“Salmon put on the bulk of their weight in the ocean and they’re bringing those nutrients back to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, as those consumers ��bring them into the forest and provide nutrients for even the smallest ��of critters like insects, which fuel the annual ��migrations of songbirds,” he said. “So they’re entirely connected to the ecosystem. The loss of any of these individual spawning populations will be a diminishment of its biological community.”

Price added that Fisheries and Oceans Canada has done a good job of protecting the species in recent years, but commercial fishing of salmon continues and the best solution might be a dramatic shift in the way we view the ��fish. “I think there’s an argument to be made that, like we ended ��whaling in British Columbia, maybe it’s time we took a step back and ��stopped exploiting species such as salmon for economic gain, keeping those fish for the watersheds that they’re returning to and providing food for local individuals and local ecosystems.”

Matt Simmons is a reporter with The Narwhal, where this article first appeared.

��