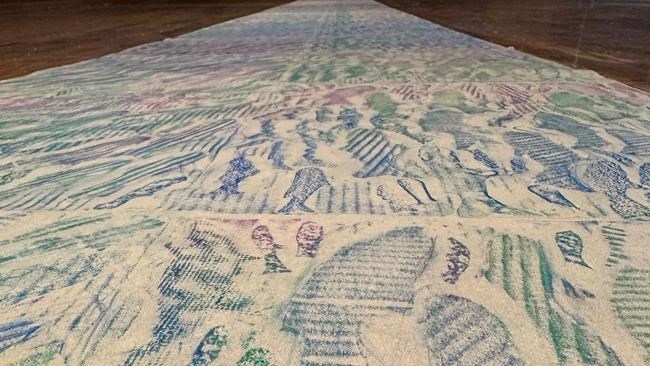

DUNCAN, –°¿∂ ”∆µ — Images of steelhead and trout flicker over long sheets of paper, brought to life in blue and green crayon rubbings by the thousands.

It's called Project 84,000, and is intended to depict the number of steelhead and trout that died in a massive fish kill in the drought-stricken Cowichan River on southern Vancouver Island last year.

Jennifer Shepherd has been managing the project, which involves a series of gatherings in the community to create the rubbings that will go on display later this year in what will be an art event, an environmental awareness campaign and an act of mourning for the fish killed last July.

“The enormity of the loss was something that really struck me," said Shepherd, a community researcher with water sustainability group Xwulqw’selu –°¿∂ ”∆µions, who said the project aimed to help people comprehend the scale of the loss of life.

"It felt really tragic and sad to me, and I thought this would be a good idea for us to mark together in the community, for us to really honour and acknowledge,” said Shepherd.

Scientists and others like Shepherd worry that climate change and the threat of another year of drought could have further dire consequences for populations of salmon, trout and other fish in –°¿∂ ”∆µ

Fisheries and Oceans Canada says climate change is affecting every stage of the life cycle for Pacific salmon, while the –°¿∂ ”∆µ government warns that drought can dry up fish streams, delay spawning migrations and kill fish in warm water. Vulnerable species include salmon and trout but also endangered species such as the Nooksack dace and Salish sucker, the –°¿∂ ”∆µ government says.

About 40 per cent of the province is already at drought level three, four or five, meaning drought impacts are possible, likely or certain. The April snow survey by the –°¿∂ ”∆µ River Forecast Centre showed the lowest snowpack on record in –°¿∂ ”∆µ, at just 63 per cent of normal, potentially increasing drought risk this spring and summer.

Fisheries biologist Tom Rutherford is the strategic priorities director for the Cowichan Watershed Board.

He said he was sitting on Emerald Glacier in the Rockies last summer when his phone started pinging with news of the fish kill back home.

He said it "seemed ironic" to be sitting on a glacier, melting due to climate change, as he heard news of what he called an "unprecedented fish mortality event."

“We've been talking about climate change now for decades and generally we've done nothing about it as a society, and now we are paying the price," said Rutherford, a former Fisheries Department biologist.

"And unless we are able to move the needle to change our behaviour around how we treat our water, how we treat our rivers, how we treat our salmon, if we can't do that, we'll lose them. They'll be gone in 50 years,” said Rutherford.

In the Cowichan Valley, community members treat fish and rivers as relatives and family members rather than resources, said Rutherford.

That made losses such as the July fish kill overwhelming.

“It's a beautiful river, but it's more than that. It's like family … and I think that’s how so many of us feel."

The Fisheries Department said in a statement that the fish kill was more likely due to “stressful environmental conditions than of a specific cause.”

Rutherford pointed to several factors, including warm river conditions with temperatures over 20 degrees, and low water flows of 4.5 cubic meters per second. He said this was the lowest the river had been since the 1950s, making trout and salmon “severely stressed."

“It's just this cumulative stress of all these things layered on top of each other,” said Rutherford.

'ALL THE FISH IN THE POOL DIED'

Shepherd said she used to hear stories from members of the Cowichan tribes of waters teeming with so many fish and you could "walk across their backs."

That is no longer the case, with declines also evident to others watching rivers elsewhere in –°¿∂ ”∆µ

In Chilliwack, about 100 kilometres east of Vancouver, lifelong salmon sports fisherman Travis Heathman said he'd witnessed a “tragic” shift watching the fish struggle to survive in the nearby Vedder River.

Heathman, 68, who started fishing the Vedder at aged 12, said drought had taken a toll, with many fish dying with unfertilized eggs trapped in their bellies.

He said the fate of fishing on the Vedder keeps him awake at night.

“My son fishes in the river, his boys fish the river and I worry about the future," he said.

“Unfortunately, I think we're gonna see a time when there is going to be a lot less fish in the river … for the generations coming up, they don't get to experience the good old days."

For Jason Hwang, vice-president of the Pacific Salmon Foundation, the impact of drought on the fish he loves has hit close to home.

Last summer, he watched as a small stream next to his home in Kamloops in the –°¿∂ ”∆µ Interior went from being full of life to drying up in just a couple days.

“And over the course of about 48 hours, all the fish in the pool died — dozens and dozens of juvenile salmon and bigger juvenile trout,” said Hwang.

Hwang said he also heard reports of many rivers around –°¿∂ ”∆µ facing the same challenge, from the Lower Mainland's Fraser River to the Skeena-Bulkley Valley near Smithers 1,000 kilometres to the north.

He said the Fraser suffered record low flow last summer. It got so shallow that water couldn't flow through a concrete fish ladder, built about 60 years ago to help salmon on their migration journey.

Only a few survived the arduous journey to spawn, said Hwang.

“They even get stuck on their migration in these medium and large-size rivers and these drought conditions are outside the range of what we’ve normally seen and our salmon aren’t adapted to it and the measures we have in place like fish ladders might not work in these kinds of flow conditions that we are seeing,” said Hwang.

Sometimes drastic action has been required. When a stretch of the Indian River in the Lower Mainland ran dry last September, stranding thousands of pink salmon, Hwang's team used an excavator to dig a trench to allow the fish to continue their journey.

Describing salmon as "a gift" to the world, Hwang said he couldn’t image a river without them.

“They support the forests, they support the eagles, they support the bears, they support the killer whales," he said. "They connect the freshwater ecosystem to the ocean, very few things can do that."

Hwang said he worried about the low snowpack, and said the foundation would have a response team prepared to take action again.

"Being ready for emergencies is a really good thing, but it's not the only thing we should do. We need to look more at the bigger picture plan, we need to change the way we use water. We need to protect our watersheds better," said Hwang.

He said it's not too late, and pointed to chinook salmon returns in the Cowichan that had recovered after years of effort.

“Salmon are resilient. If we start undoing the things that we've done to cause them harm and we manage our natural resources better, they can recover,” said Hwang.

As for Shepherd, she hopes that Project 84,000 will help open people's eyes to their own relationships with fish and the waters they rely on. The finished work goes on display in the Cowichan Valley Arts Council Gallery in Duncan this fall.

"Water is life, water is our kin and the water is the home and habitat for more than fish. We are all connected, everything is connected," Shepherd said.

“And what might we choose to change in terms of our beliefs, our attitudes and our actions individually and collectively to preserve the health and wellness of the fish, the water, the watershed and ourselves?” she asked.

"Starting from that place of understanding, then we can look at one of the impacts of our choices."

— By Nono Shen in Vancouver

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 8, 2024.

The Canadian Press