This weekend, one of Vancouver’s oldest buildings will be knocked down.

Standing on the street to watch an excavator complete the task will be Saul Schwebs, the city’s chief building official, who recommended to council in December that the 1908-era five-storey building at 500 Dunsmuir St. .

Through a series of slides showing the poor condition of the inside and outside of the building — commonly known as Dunsmuir House — Schwebs emphasized the urgency to demolish the former grand hotel.

“This building is in a very unstable condition,” he said at the time. “We've already seen limited collapse inside. Some of the concerns we have are, is if one more floor lets go, it might take a portion of the wall with it.”

Schwebs used the word “frustrated” to describe losing the 167-room building, which last served as social housing until a lease between owner Holborn Group and 小蓝视频 Housing ended in October 2013.

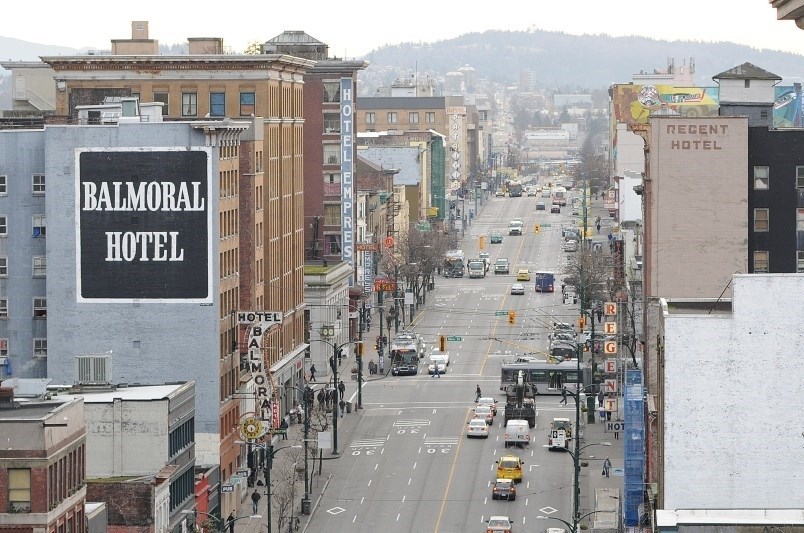

That frustration has its roots in what Schwebs described as a life-changing experience that dates back to April 2017 when he visited the on East Hastings Street, near Main Street.

What he saw was drug use, tenants in poor health and wall-to-wall poverty amid deplorable and unsafe living conditions. The Balmoral was later purchased by the City of Vancouver, which led to its recent demolition.

“I was frustrated in that moment because that was a building the city inspectors have been going in and out of for 20 years — and it was still in this condition,” he said, referring to the decades of violations against the Sahota family, which owned the Balmoral.

“It was brought to the point where it was structurally unsound. So that kind of spurred me on and really leads me — inspires me — in my service to this community to try to make sure that we have safe housing for everybody, especially the most vulnerable.”

It was a rare personal anecdote shared by a city staffer in the council chamber.

The moment prompted BIV to learn more about Schwebs, who is originally from a small town in Wisconsin and is now a Canadian citizen. He is a trained architect, who last worked in that capacity at a high-end design firm in West Vancouver.

“I was spending my Sundays working on a billionaire’s 14,000-square-foot vacation home in Maui, across the street from his 10,000-square-foot vacation home,” he said. “And I thought: ‘This is not how I want to spend my time.’ So, I started looking for something closer to my values.”

In a wide-ranging interview this week, Schwebs talked about those values, his rise to chief building official, the task force being created to focus on vacant buildings and why he left the United States.

He even entertained a question about the television series, Better Call Saul.

The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Let’s get to some of your biographical information first. Where are you from, and where did you go to school to prepare you for your current job?

I was born and raised in Wisconsin. I got my Master's in Architecture at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Then I started my career in Chicago working in architecture offices. I had the good fortune to be able to spend a lot of time on site, which a lot of intern architects don't. I was able to engage with the contractors and watch what they're doing on site. I learned a tremendous amount that way. Over the next 20 years, I worked on a variety of different building, types and sizes.

Why did you leave the United States?

Because George W. Bush got re-elected.

Really?

Yes, I’m one of them [who left the U.S. for political reasons]. I wanted to leave the first time he got elected. I have my bachelor's in political science. I saw a worrying change in tone and how he got elected the first time. That was only reinforced when he was re-elected. At that point, my wife at the time had just gotten laid off. So I said, ‘OK, let's go.’ I wanted to come to Canada because I thought it was better in line with my values, and with the values I wanted to raise my kids with. And it's worked out really well for us.

When did you leave the U.S.?

We moved up here in October 2005.

What did you do after you left the design firm in West Vancouver?

I ended up in a sustainable consulting firm for a couple years. Didn't really like that. Then one night, I decided I was going to try to be a building inspector. Got a position as an auxiliary building inspector with the City of North Vancouver. Really loved it. Then got a job in 2014 as a full-time temporary building inspector with the City of Vancouver. Eight years later, I was made chief building official.

I read on your LinkedIn page that you studied at the École Spéciale d’Architecture in 1998 in Paris. What was that experience like?

It was fascinating. I spoke enough French to get by. I remember one night I was looking at one of my favourite buildings in Paris — Saint-Sulpice — which is mentioned in the Dan Brown novels. There's a really interesting detail on the back that I discovered. I was going home from a pub one night and I showed it to a classmate. We were just marvelling at it, trying to figure out how it works structurally.

And a local woman asked what we were doing. We said this is a really interesting detail, and we’re not really sure how it's held up structurally. She asked, ‘Well, how old is it?’ ‘I don’t know, ‘I said, ‘18th century?’ She looks at me and says, ‘Well, so it's new then,’ and walked away. It's got two towers, and one's not finished, and it never will be because the people who can finish it died a long time ago. I just think there's something beautiful about that.

Can you explain to readers what your job entails as the city’s chief building official?

I am the final arbiter of all things related to buildings, and building safety in the City of Vancouver. I am an independent statutory decision maker, so I have final say on what goes into the Vancouver bylaw, which is a great place to be. I can push an agenda as far as things I want to see in buildings from a sustainability or seismic resilience standpoint.

You mentioned to city council in December that you’re “in the bylaw compliance business, not the punishment business.” What powers do you have as the city’s chief building official?

My job is to ensure people are safe when it comes to buildings. That's the fundamental thing. I have the authority to address unsafe conditions under the building bylaw. I have the authority in certain cases to take immediate action in the bylaw without even letting an owner know. So I have some pretty big hammers. Compliance is always the goal. Enforcement is a tool that we have to gain compliance. We start with education and try to get voluntary compliance, and we escalate from there.

'It was heartbreaking'

Tell me more about your visit to the Balmoral Hotel in 2017.

I'm from a small town in Wisconsin, lived a life of relative privilege. Two loving parents sent me to college and whatnot. I had a certain image of the world. I moved to this beautiful City of Vancouver, one of the most livable cities in the world. Then I was shown what's going on inside the Balmoral, and it was heartbreaking. I saw beautiful young people shooting heroin in the middle of the day. I saw floors covered in feces and blood, needles everywhere. It was just awful.

In this position, I have an opportunity to do good. Years ago, the city had what was called an integrated enforcement team, which was a team of inspectors who were seconded under one supervisor for a year. They would work on our most problematic case files. We’re revamping it and calling it the integrated compliance team because I want the emphasis on the goal, not the tools.

So that’s different than the task force I’ve heard about regarding vacant buildings?

Yes. We just had a meeting with the team Jan. 13. We had met a couple times this summer. We're kind of figuring how to start small and how to do some of the prep work, and then we'll begin that bigger group. But I think part of one of the first things we're going to need to do is we need a bylaw specific to the maintenance of vacant buildings.

In having spoken to our legal department, I don't think we have the authority under the Vancouver Charter to do that. So it's going to start with a Charter challenge. So I'm going to start moving forward on those pieces while we're developing the working structure of the vacant building task force. I'm hoping to make some significant strides this year.

Any idea how many unoccupied buildings there are in Vancouver that are in similar condition to the one at 500 Dunsmuir St.?

At that level of disrepair? I'm hoping it's none, or a handful. But quite honestly, like we just don’t know right now. So that's going to be part of the urgent work of this task force.

'Cities shouldn't be museums'

You’ve talked about the frustration of having to order the Dunsmuir Street building to be demolished. Is this personal for you?

Anybody here at the city will tell you I'm not a huge heritage proponent. Cities shouldn’t be museums, they need to shelter people. The fact is this building was an SRO for years before it was vacated in 2013. That tells me that in 2013 it was still fit to provide housing.

And over the course of the ensuing 13 years, this city has been going through a housing crisis and homelessness crisis — and any number of other crises — and this building has sat there vacant. I needed to go see for myself if there's anything that could be done with this building. It’s only personal in that it evokes a strong emotional response knowing it couldn’t be saved.

Is the Dunsmuir the worst building you’ve been in? Or is there another one?

I would say the Dunsmuir was maybe the worst one. Another one that was almost as bad, but just a much smaller building, was at 26 East Hastings. I got a call from VPD. A couple of constables stopped in because some of the hoarding in front of the building had been pulled off, so they went in to investigate. Then they called me.

I forget the name of the restaurant that was there, but the second floor had collapsed into the basement. So the first floor was gone. The second floor was gone. The basement was flooded. The big cooktop at the front of the restaurant was sinking into the floor. So that one had to come down in a hurry.

I wanted to talk to you about the Winters Hotel fire of April 11, 2022. Two people died in that fire — Dennis Guay and Mary Ann Garlow. There were numerous recommendations from the coroner’s inquest directed at the City of Vancouver. What did you learn — or the city learn — to ensure such a tragedy never occurs again?

I remember Mary Ann was a resident of the Balmoral, and I was part of the city action that evacuated that building when we determined it was unsafe, and we moved her and her son into the Winters. So I think about that a lot. We just have to do better. What did we learn? We learned an awful lot.

Such as?

One of the things that's already put in place was an idea from Deputy Chief Rob Renning of Vancouver Fire Rescue to add isolation valves to the sprinkler riser in all residential buildings in the City of Vancouver. If you remember with the Winters, there was a fire [a few days before the big blaze] that was contained in one suite. It wasn’t a major fire, but it did cause the sprinklers to activate.

When a sprinkler in an old building like that activates, it runs continuously until the fire department shows up, finds out where the valve is, goes down usually into the basement and finds the valve and shuts it off. That leads to an enormous delay. They shut the whole building down, and it can't be turned on again until that head is replaced.

On the morning of [the big fire], the department was on its way there to replace that valve when the fire started. So this new bylaw requirement with isolation valves on each floor means that if a fire were to happen, a firefighter would be able to go to the stairwell on that floor and shut off the sprinklers for just that floor. So we’re helping to limit the risk.

What else are you doing to prevent such a tragedy?

One of the things [the coroner’s inquest] asked us to do is put together a database. All of the agencies that have input with these buildings — fire, VPD, us and hopefully even Vancouver Coastal Health — can start adding information to this database on these buildings. Had anybody known that Dennis Guay was hearing impaired, and it was in somebody's action plan to go knock on his door, he might have been saved.

If we can get operators to tell us where folks with different abilities or disabilities are in their buildings, that can be helpful. There's some privacy issues with that, of course. But it's just one thing. We want to come up with ways that we can find the problem or learn about the problem without hearing after it when it becomes a problem.

How we do that? I'm not sure. There's a whole lot of work, but I think the council support is going to be huge to help getting things done.

Before I let you go, I’ve got to ask: I'm sure you're familiar with the television series Better Call Saul. I'm wondering if the title of the show has been a line people use when they have concerns about a problem building — that they better call Saul?

A colleague in engineering told me the other day that ‘better call Saul’ has become a common refrain/running joke when they’re dealing with a question related to buildings or private property. I’m the first person that gets called on a lot of issues. But I do love the show. For the record, I would like Bob Odenkirk to play me in my biopic.